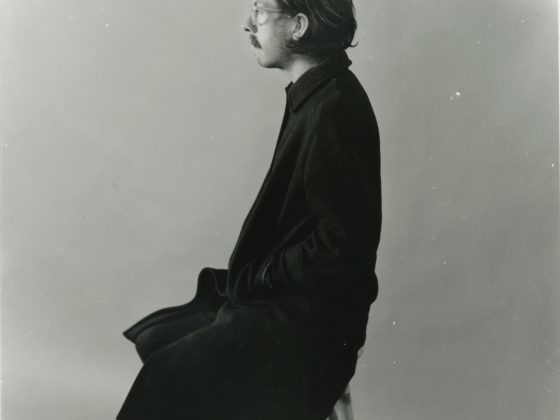

Resembling a romantic poet of England’s dusty past, charming and affable Cure keyboardist, synth aficionado, and composer Roger O’Donnell has recently unveiled his latest project 2 Ravens, a melancholic and pastoral corvid inspired collection of songs that are the perfect soundtrack for gazing out a rainswept windowsill; whether it be during the sanguine era of Victorian consumption, or under quarantine in the time of Covid-19.

The album 2 Ravens came to be following the conclusion of two events: The first being the O’Donnell’s surprising stint as an Executive Producer of a Morrissey biopic, and the second being The Cure’s sprawling 2016 world tour.

Returning home to the idyllic countryside of Southwest England, O’Donnell began to germinate the seeds of his next solo record, while his band started the slow process of finally following up 2008’s 4:13 Dream, this time on their own terms.

O’Donnell recently updated the NME on the status of the new Cure record, stating:

“We’re finishing the record, it’s pretty much done. Whenever Robert does an interview, it’s interesting for the rest of the band to find out what we’re doing as well! But we’re just mixing and mastering the record now.

“There’s no rush, is there? It’s been 12 years. It is an amazing record though and totally worth waiting for. We’re very excited by it.”

While we wait for The Cure to wrap up production on the new album—which was initially set to be released this past December, O’Donnell has finished his own—and it opens with the sheer aural beauty of a track named after that shivering winter month, invoking the gothic beauty of This Mortal Coil on their later two classical music-oriented records Filigree and Shadow and Blood.

We spoke to O’Donnell on the development of this record, and his love of synths, cellos, pianos, and more, working with Vita and the Woolf’s Jennifer Pague, and playing keys on some record called Disintegration that you may or may not have heard of…

See our interview with Roger O’Donnell below:

You grew up with a musical background, didn’t you? As opposed to just going out and joining a punk band. Did you study how to compose music before you ever performed?

Yeah. I mean, I was at art school when punk happened. My best friend Ian Wright, who did the cover art for [2 Ravens] came to me one day with a Sex Pistols flyer, I mean, Wow. Great name for a band, and the flyer was two cowboys with their dicks out. So it was like, nineteen seventy-five. And It had a huge impact on everyone. I think, you know, music that was going on, at the time was prog rock and then pop-rock. And it was pretty awful. So I mean even if you weren’t really into it had an effect on everyone. I think it had a huge effect on, what everybody thought about music, About how everyone thought if they could be in a band or not. I mean, it made everyone think that they could actually do it, compared to, mega-rich guys in bands like. Yes. And Genesis and all the rest of it.

So, it was a really inspiring time. But, even though I played, I didn’t fit only because there were not a lot of keyboards in punk.

Can you tell me about your involvement in being a producer for the Morrissey film England is Mine.

It was a friend of mine, Orian Williams, who produced Control. You know, the Joy Division Movie. We’ve known each other for a long time. And we were we’re always talking about my investing in a film. And that opportunity came up initially because of the kind of animosity between The Cure and Morrissey or between Robert and Morrissey. It seemed a bit politically difficult for me, but in the end, I was happy to be a part of it. I didn’t think that it was a great film. I think that it really, after Billy Duffy left, seems to fade away.

The story wasn’t great. It wasn’t well-received, but it was an interesting process for me to be involved in.

Did Morrissey approve of the film?

Yeah, [Morrissey] gave it his blessing, and we desperately wanted to put a Smiths song over the credits. And I think that would have been really good. But Johnny Marr blocked it immediately without any discussion.

So, you know, there’s politics between those guys and they probably wanted too much money, it was a low budget. It cost 1.2 million, I think. So we probably didn’t have the budget for it even if they said yes. Morrissey wasn’t pissed off about it. And like I said, he wished it well. I don’t think he’s ever seen it. But from day one, I don’t think it portrayed him in a bad light. I thought of it as if that were me, I wouldn’t have minded.

The director Mark Gill, you were looking at a new project with him and that’s where the idea for 2 Ravens Project came from?

Yeah. We had talked about doing more of a collaboration rather than me just writing the soundtrack for a film about the life of Masahisa Fukase.

He was a Japanese photographer and his book was called Ravens. And he used to take photographs of his wife every day. And she said, like, you know, stop fucking taking photos of me, I’m going to leave you. And because he couldn’t, she left him. And then he started taking photographs of ravens. And they’re really beautiful photographs.

Then he went to this bar and he said to the bar, “one of these days, I’m going to get so drunk. I’m gonna fall down the stairs, and I’m going to die.” And it happened—he fell down the stairs.

He was in a coma and his wife came back and visited him every day. So it’s kind of a really interesting story. And the imagery obviously lends itself to taking the imagery from the book, that kind of approach to it. And I think that was in the back of my head when I first started writing.

Also, I wrote one of the songs [on the album] called “The Hearts Fall” based on a poem by Ted Hughes. He was married to Sylvia Plath, and she’s like a goth icon. He wrote all these kind of brutalist poems about nature and specifically about crows and ravens, So there is poem is called “The Crows Fall”.

I met Philip Glass in March of 2016, and he asked me to write something and perform one of his Tibet concerts, charity concerts. And I wrote that. So that was kind of also a basis for the start of the album.

The record gives me the kind of pastoral, melancholic feeling I get when I listen to Chopin.

On tour in 2016—and for pretty much the whole tour—being around people all the time, I was just longing to be home. While traveling and you know, you never get to make your own food. Then in December, the tour finished. I got to go home. I live in the middle of nowhere in the English countryside. And suddenly I’m at home enough and after longing for this solitude— I started feeling distraught with loneliness.

And I’m surrounded by the countryside in midwinter, which is pretty harsh. This is very black and white and gray. There’s no colour. I find touring really the opposite of creativity, you know, it’s just you go out and you play songs, but it’s a big drive for me personally to create music.

So I had all this kind of pent up creativity and then being surrounded by this melancholic ambiance and scenery. And that’s the way it came out. So it’s really cool that you can get that. If you can do anything as a musician or as an artist, if you can convey the atmosphere that you are creating within to somebody else without words, that’s really priceless, I think.

It reminds me of a quote from the movie about Beethoven, Immortal Beloved, about putting the listener into the mind of the composer.

Oh, thank you. I wouldn’t…I’m not sure I would want to be in Beethoven’s head though!

There’s also that question – if you actually get to know a composer, sometimes it’s better to just have that mystery of just the music or not to know. And, if you’re going to understand anything from that creativity, it’s best just let the art speak. I think that’s often the case with musicians and creative people. As soon as they open their mouths, things go downhill.

Speaking about being isolated and creating Art, is it déjà vu with how you’re coping with what’s going on right now?

Well, luckily, my girlfriend is here. I don’t know if it is lucky for her, she’s probably going insane [laughs].

She is in the countryside with you and not back in Berlin?

Exactly. She has an apartment in Berlin. And I don’t think you’d want to be locked down in an apartment. I can imagine how difficult it is for a lot of people that are in that situation.

I mean, we’re lucky. We’re surrounded by open fields and I’ve got a big garden. So, we’ve been doing a lot of gardening and we’re actually talking to each other, which I think is a bonus.

It’s a real test of a relationship. Love in the time of COVID-19.

Yeah, we’re doing pretty good. She got a bit depressed this afternoon and I rallied around and then I was depressed the other morning.

I mean, it’s crazy. She knows what’s happening. And people keep saying to me, “be really good. It’s time to be creative.” And it’s kind of the exact opposite because I think, speaking personally, creativity breeds off of pressure. And when you’ve got absolute freedom, I mean, I’ve got all day. And we’ve just decided that every day’s Monday from now on. So, you know, because each day is no different. So, I could spend all day, every day in the studio. Yet I just don’t. I’m just not feeling it.

So I wanted to ask you about synthesizers. We know you’ve been to Berlin. There’s been a big synthesizer trend there for years. There are workshops everywhere. But in back in the day, you were a noted fan of Sequential Circuits. Did I hear you had a record for having the most on stage at any given time?

Yeah, there’s a really nice little book that this New Zealand guy wrote about the story behind Sequential Circuits and the Prophet.

When I first started playing keyboards, I had a Fender Rhodes, and then the Moog started to come along but couldn’t afford a Mini Moog at that time. So I decided I was going to get a job and earn some money and buy a synthesizer and Sequential Circuits just…And at that time there wasn’t a polyphonic Moog, though. There wasn’t a lot of choices. I loved the sound of the Prophet Five. So, I was able to buy a Prophet 600. I don’t want to get too geeky on you, but the Prophet 600 was the first instrument that had midi on it. So, it was quite a groundbreaking instrument. And from then on, I bought a Prophet T8. And you know, I just kind of went down that road. I mean, if Moog had been making polysynths at the time, I probably would have been playing them. But I had a good relationship with the guys at Sequential and subsequently, I mean, in more recent years…in the last fifteen years. I’ve become very good friends with Dave Smith, who started the company. He’s a super nice guy.

I’m also very close with a guy at Moog. And I just got a Moog One, which is the big deep poly, which I’ve been working on with them since 2006 I think.

Can you tell us more about your relationship with Moog?

I’ve been discussing it with the head of design. In fact, he was supposed to be coming out to England. And he was gonna spend a day with me going through the [Moog One] but of course, probably not at the moment.

I was asked to do a song for a documentary that was made about Bob which was luckily made only a year before he died. I wrote a song for it and I thought it’d be nice to try and revisit my early days of just using Moog monophonic synth to orchestrate things. I did the whole song using the Moog.

I’ve met the guys and became really good friends with them. And yeah I did two albums that were just recorded using the Moog Voyager.

And I say, Moog. I know in America. Everyone calls it Moog. But if you say that in England, everybody just thinks you’re being pretentious. So, It’s really hard for me to break out of it.

Can you tell us about the piano on 2 Ravens?

This album, the piano on it isn’t real. Well, it is, but it’s sampled piano. It’s a plugin for Logic called Ivory. And it’s made by a company called Synthogy, And the actual piano that I’m using on this record is the Steinway, the new Steinway. That’s at Carnegie Hall. That was just restored and reconditioned. I’ve got a Steinway in my living room, but it’s out of tune, obviously, because the piano tuner won’t come and it’s really hard to mic, and these guys go to so much infinite detail of catching sounds. You’ve got pedal sound. There’s sustained resonance. It’s just unbelievable. And my mastering engineer Guy at Electric Mastering in London. He can’t tell the difference. And he’s got the best ears that I know.

So, it gives me the freedom to be able to edit while I’m playing and work in a way that I’m more comfortable with. I guess when you’re in the studio and that red light goes on, I think it instantly kind of clamps you up somehow.

I can record the piano at home, and I’m really comfortable with it. And that’s really the basis for the songs as well. The emotion for the songs. So it’s really important I’m comfortable and can play in a way that I feel I can express myself.

Although there’s nothing there’s nothing that compares to sitting in front of a grand piano. That’s just, you know. And I do I play every day.

Can you tell us about your use of the cello on 2 Ravens?

Such a beautiful instrument. It’s the closest instrument to the human voice because its range is very similar to a tenor. And for me, it’s just the most expressive instrument, the most emotional. And having worked with it over the last ten years very closely and the musicians that I use, Miriam and Alisa, if I could play the cello, I would play as they do. And when I give them the piece to play, they just play it how I hear it in my head. So it’s a very easy process to transfer from. I write using cello samples and then I score it and give it to them. And it just sounds well, it’s just how it should be.

It’s a very easy process working with them.

How is it working with Jennifer Pague?

Well, we didn’t meet—we didn’t actually speak in the beginning. I first met her when we went into the studio in London to record strings and vocals. I was introduced to her by my publisher, who also publishes Vita and the Woolf, her Project. And he suggested adding vocals on some of the songs just to make it a little more accessible. And I was like, yeah. I don’t mind. Well, let’s try. I’m not guaranteeing that I’m going to like it or accept it. So we sent her one song, which was “An Old Train,” and she sent back about 30 seconds of it within a day, I think, a day or two. And it was just again, it was like, wow.

It was like another instrument. It just worked perfectly. And it’s quite different to her project, to Vita and the Woolf, which is a little more kind of rocky and anthemic kind of Americana. And I was really intrigued by the contrast between her American aesthetic with the lyrics, her phrasing, and the very European approach to the string quartet and the piano and cello. Although having said that its European. It’s not I mean—there’s plenty of great classical musicians in and outside of Europe.

But, you know, I mean, the kind of old-world sound of the acoustic instruments and the Americana of her. And I just thought that added such an interesting layer to it.

Can you tell me about the video for “The Haunt”? It reminds me of Berlin with the city’s trademark dark staircases.

We shot that in Friedrichshain up in Mimi’s apartment building. So it’s very old school, East German. An East German apartment with loads of stairs. And we did it with the lights turned off with our iPhones. And then, of course, the neighbors came out and wanted to know what was going on.

We shot it really quickly because I don’t have much patience for anything, really, though, we shot it, and then it took a lot of editing to get the kind of flow on, to get things to build. And I kept giving up on it. And then we thought we’d reshoot it. But in the end, it worked. And it’s good that it makes you think of Berlin.

Can you tell me about the Post Romantic Empire album?

Yeah, that was a weird one. A friend of mine, that promotes concerts in London, an Italian woman who’s really interesting.

Clarita. She knew this guy who had this idea for a project. And it was to re-imagine a song or a piece of music. And he wanted me to re-imagine it just Sheherazade. And I was like, oh, this is weird. How am I going to do this? And you’re supposed to work with somebody else and then give the whole thing to somebody else. It was a weird, long-winded process, but in the midst of it, I met Julia Kent, who played cello on it. We came up with the idea to make into an album, and that’s kind of what led me on to doing piano and cellos.

Last year was the 30th anniversary of Disintegration, and you performed those concerts at the Sydney Opera House with The Cure. How was it working on that album? You wrote or co-wrote “Out of Mind” and “Fear of Ghosts”, Correct?

Oh, I wrote “Fear of Ghosts” and “Out of Mind”. Yeah. I mean, it was weird for me, like, I was kind of a full member of The Cure before we started making that record. and Robert said, “OK, I want you to bring demos for the next album”. And I was like, “OK”.

And so we all got together in the house, not very far from where I live now, and played our demos. And then the ones he thought he could sing on were chosen. I mean, I was blown away that two of mine were chosen as b-sides. So it was pretty cool.

Did you have any influence on thematic elements on that record?

Well, I played all the keyboards on it. I mean, I just was responsible for the sound of the keyboards. So it depends on how much credit you want to give me.

But I do remember we were at a party before we started recording and Robert came up to me and was like:

“I’m just really looking forward to recording this record because I don’t have to get involved in playing keyboards on it and concentrate on the guitar.” And he said: “I’m just really happy that you’re gonna be here. So I said: “Yeah, I’m pretty happy as well.”

The Cure have been very supportive of younger bands lately. What were your thoughts on that, and what would be your advice to those who would get into music?

I’m still going up to the people that influenced me and telling them if it wasn’t for them, I wouldn’t be playing music. You know, whenever I meet artists, especially someone like Herbie Hancock who was hugely influential on me.

And so when somebody comes up to me and says that to me. It still really confuses me, because I still think of myself as being in their place. But the only thing I can say to a young musician is you better really love it. It had better be a passion. You better not be doing this for any other reason because it’s going to suck the life out of you. It’s going to destroy you at times. But you’d better just want to do it, you know. Otherwise, you’re not going to survive. Go on and do something else keep it as a hobby because it’s always been tough. You know, people talk about it being tougher now.

It’s tougher in some ways, and easier in others. It’s never been easy, so you better really, really want to do it.

Oh, I wanted to ask you, what are you reading on the U-Bahn platform in the video for “An Old Train”?

Well, it was a nod to Jen. It’s a Virginia Woolf book. This was a nod to her band Vita and the Woolf.

2 Ravens is out now via Caroline International and 99X/10.

Or via:

Or via: