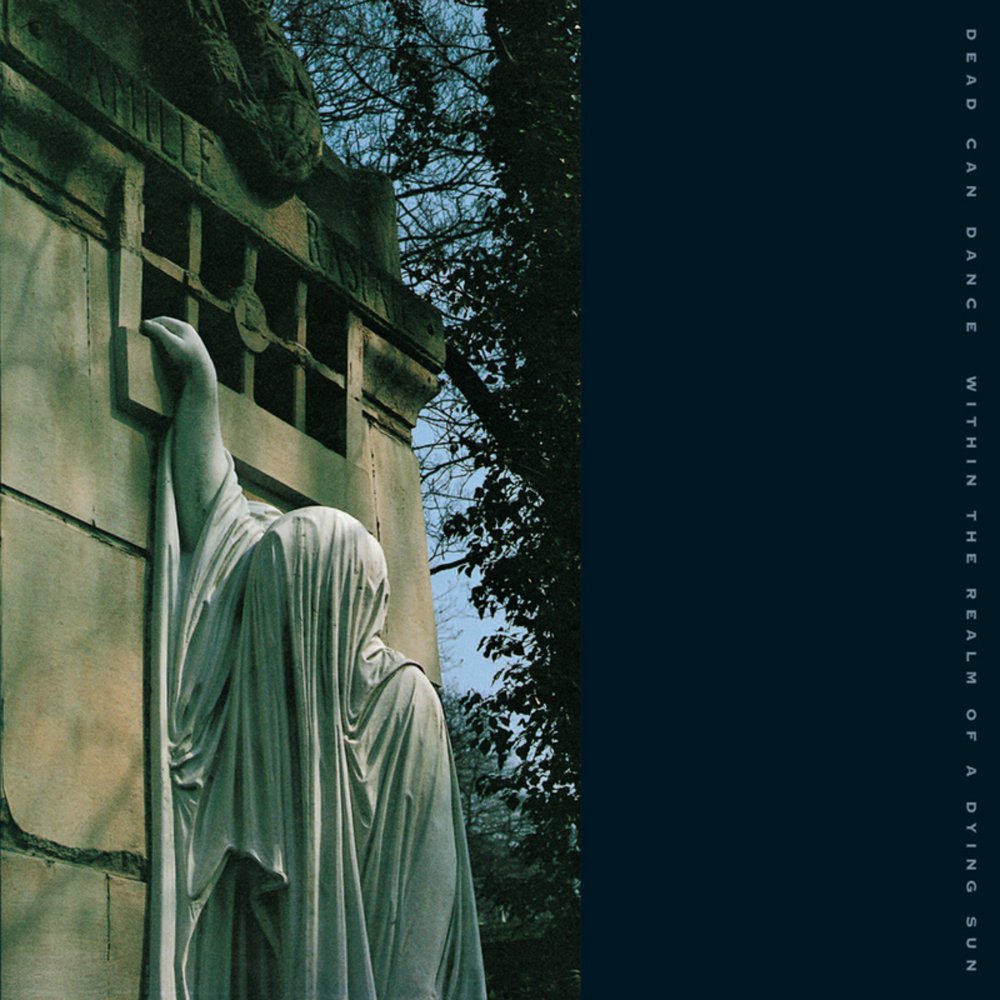

On July 27th, 1987, Dead Can Dance released their third studio album Within the Realm of a Dying Sun, a record which pared down the band to be predominantly the core duo of Lisa Gerrard and Brendan Perry, and percussionist Peter Ulrich, after the departure of Scott Rodger and James Pinker in 1987.

The album’s iconic cover photograph was taken in Paris at the family grave of François-Vincent Raspail at the world-famous Père-Lachaise cemetery where artists such as Jim Morrison and Oscar Wilde were laid to rest.

The first half on the record features primarily Perry on vocals, closing out with the dreamlike chiming of “In the Wake of Adversity” fan favourite “Xavier”.

These were the sins of Xavier’s past,

Hung like jewels in the forest of veils.

Listen to “Xavier” below:

The second half of Within the Realm of a Dying Sun, led primarily by Gerrard, begins with the short “Dawn of the Iconoclast”, which then leads into the spellbinding eastern mystique of “Cantara”. This is unrelentingly followed by both the cathedral-like litany of “Summoning Of The Muse”, and the stark and otherworldly ritualism of “Persephone (The Gathering Of Flowers)”.

Listen to “Cantara” below:

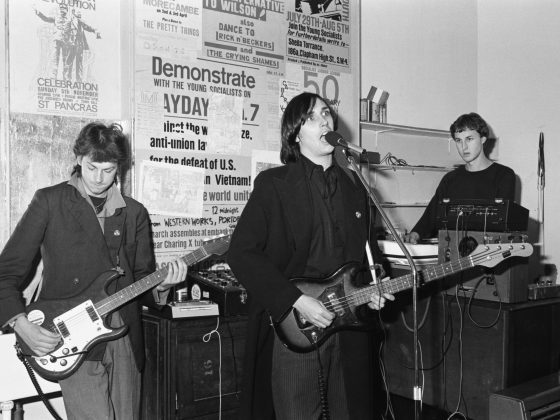

In a recent interview with Post-Punk.com, Brendan Perry noted the progression of Dead Can Dance’s sound from the first album to Within the Realm of the Dying Sun:

“I think that each album is a direct result of a period of time where we just immersed ourselves in these different musics. After the first album for instance, which was more post-punk, we would go down to this music library close to us where we would go down twice a week and get these classical vinyl records, borrow them, and listen and tape the ones we loved on cassette. That’s all we would listen to for a year and a half, and out of that came our new baroque second album Spleen and Ideal, and then Within the Realm of a Dying Sun, which is more of a romantic classicism.

We found this really reflects our immersion and passion for whatever musics we were listening to at the time, or literature, or cinema, or any other cultural inspirations. Behind it all essentially, that’s the binding concept in the spirit of our own work. In a global sense, we look for what is universal in these different cultures, in an existential context. “Who are we,” you know, and as Gauguin said, “where are we going?” We’re drawn more towards the things that connect us and things that we all have in common as opposed to what makes us different, whether that be race, nationalism – all these artificial constructs really don’t interest us. That’s really the inspiration behind our genre wanderlust and how we work.”

Or via:

Or via: