“The notes just came out. David was stunned, as was I. The hair on his arms was up and he had tears in his eyes: ‘I see Twin Peaks. I got it.’ I said, ‘I’ll go home and work on it.’ ‘Work on it?! Don’t change a note.’ And of course I never did.”

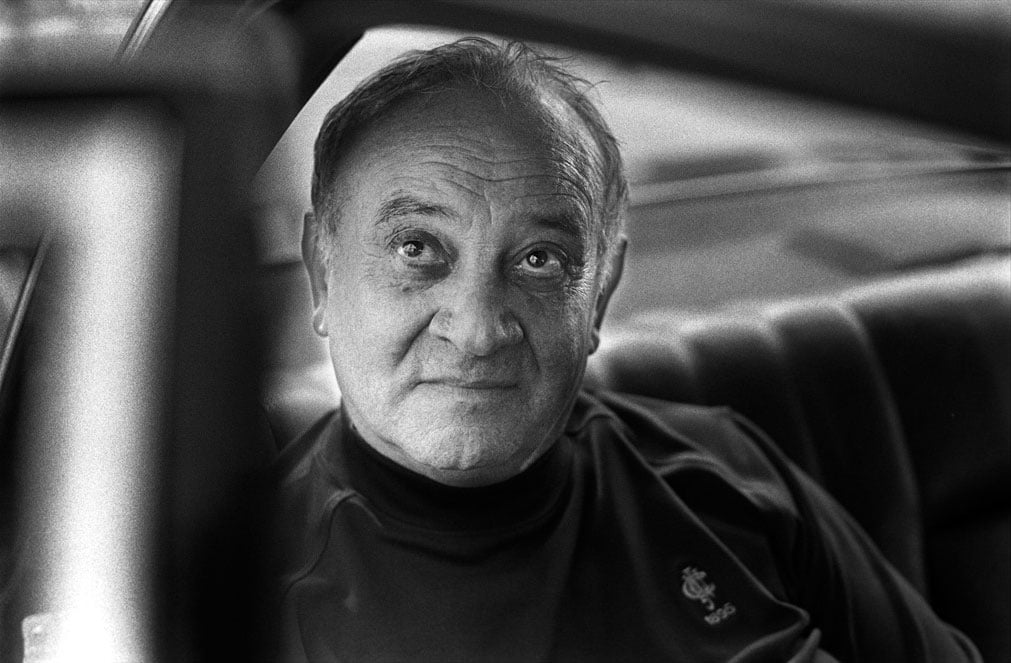

The great Angelo Badalamenti has entered the White Lodge, seated, we imagine, in those black chairs, talking backwards with Julee Cruise and the recently-introduced Al Stroebel. The 85-year-old composer passed away of natural causes at his home in Lincoln Park, NJ, survived by his beloved wife, Lonny, an artist whom he married in 1968, his daughter, and his niece.

We have penned so many obituaries for lost musicians and artists over the years, honouring those who travelled back home through the ether, thinking about the importance their music was to so many of our readers’ hearts – moments of pause and reflection for how their work makes people feel. But as soon as I heard the news of Badalamenti’s death, I sat stunned on the train: head swimming, phantom notes swimming through my head; forming around my aura. Globes of unshed tears pooled until my eyelids could no longer contain them, and I apologized to my friend, wondering aloud why my reaction was so profound. She simply said, “He touched your soul.”

Angelo Badalamenti could exquisitely translate images and mood into deeply emotional music in every one of his undertakings, but with David Lynch he found his perfect artistic counterpart. In high school, I found the Twin Peaks soundtrack cassette at Goodwill and played it every night when I went to bed; it became ingrained in my own subconscious. So many bands who we write about cite the magic that emanated from Badalamenti’s Fender Rhodes electric piano as inspiration; his deeply-charged synth music has even inspired a whole subgenre of Lynchian tribute acts in NYC. “Laura Palmer’s Theme” is quite simply the Dark Night of the Soul experience distilled into pure sound: a weary, abused spirit looking for the light; finding moments of hope, and sadly returning to Purgatory.

Angelo Badalamenti’s music, coupled with David Lynch’s visuals, was transformative and spanned generations. There was nothing like his music on television in 1990 – or, really, since. TV soundtracks at that time were primarily bombastic Mike Post compositions for buddy cop shows; saccharine sitcom jingles, or manic kid show themes. The music of Twin Peaks was something more metaphysical, a serene, cinematic soundtrack seemingly channeling Spirit itself. It became synonymous with the characters’ personalities: Audrey’s Theme being mysterious, dreamy and a little mischievous; Laura Palmer’s funereal march toward glorious redemption, the bluesy interludes alluding to film noir and 50s teen movies; the theme song itself an absolute masterpiece of synth heaven; a trap door through the crown chakra. His work often serves as the link between the mortal and spirit world.

Tapping into the collective subconscious was Angelo Badalamenti’s most profound gift; a Jungian phenomenon that unearthed emotions from the masses long after ABC cancelled Twin Peaks. When explaining how collaborations worked, Badalamenti recounted that he usually only worked directly with emotions described by Lynch, without even seeing the footage. This was extraordinary for a film composer, who usually glean their emotional connections from the imagery of the acting. These two worked in reverse.

Badalamenti’s talents were evident from the get-go. Born the son of a Sicilian fishmonger and a seamstress in Bensonhurst Brooklyn, Badalamenti’s roots in music ran deep: his uncle, Vinnie Badale, played trumpet for bandleaders Benny Goodman and Harry James.

He played the French horn in high school and later attended the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, on a full scholarship, later graduating from the Manhattan School of Music with his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in 1960. For a while, he taught seventh-graders at Dyker Heights Junior High in Brooklyn. While there, he composed a Christmas musical that wound up being telecast in 1964 by PBS station WNET, which kickstarted his career. During his youth, he would also accompany performers at Catskill Mountain resorts. “I had to play a lot of the standards, so I learned quite a wide range of music,” he said in 2019. “I had to learn them very quickly, and learning so many different types of music was a tremendous help later on in my career.”

He later worked at a music publisher, penning songs for Shirley Bassey and Nina Simone, as “Andy Badale.” His first foray into film scoring was for 1973’s Gordon’s War. In 1986, Lynch needed a vocal coach for Isabella Rossellini for his upcoming film Blue Velvet. He had heard that Badalamenti had a great reputation for working with singers.

“I met with Isabella and after a couple of hours with a piano and a little cassette recorder, we got a decent vocal,” he recalled in a 2015 interview. “So we go over to the set where David is shooting the last scene…He puts on the earphones, listens to the recording and says, ‘Peachy keen. That’s the ticket!’”

After Blue Velvet, he said, “David came to my little office across from Carnegie Hall and said, ‘I have this idea for a show, ‘Northwest Passage’ … he sat next to me at the keyboard and said, ‘I haven’t shot anything, but it’s like you are in a dark woods with an owl in the background and a cloud over the moon and sycamore trees are blowing very gently’ … he said, ‘A beautiful troubled girl is coming out of the woods, walking toward the camera …’ I played the sounds he inspired…The notes just came out. David was stunned, as was I. The hair on his arms was up and he had tears in his eyes: ‘I see Twin Peaks. I got it.’ I said, ‘I’ll go home and work on it.’ ‘Work on it?! Don’t change a note.’ And of course I never did.”

Northwest Passage was later renamed Twin Peaks.

David Lynch tried to get the rights to use This Mortal Coil’s “Song to the Siren” in Blue Velvet, but with licensing fees being prohibitive, they had to stick to an in-house approach. Badalamenti and Lynch co-wrote an original piece, “Mysteries of Love,” which was performed by the composer’s friend, Julee Cruise.

In a 2014 interview with Post-Punk.com, This Mortal Coil’s Robin Guthrie explained the situation: “(Lynch) actually asked me and Liz to be in the film. We were going to be standing on stage in the background performing it…but it all got blown up because Ivo at 4AD; I guess he was in control of the This Mortal Coil project, and he just asked for way too much money…I regret that because that would have been really cool to be in a David Lynch film, wouldn’t it!”

It would have been a sublime moment, but 4AD’s unfortunate mistake ultimately led to one of Badalamenti’s most profound compositions. In typical Lynch fashion, he set the scene with this suggestion: “Oh, just let it float like the tides of the ocean, make it collect space and time, timeless and endless.” Badalamenti had the unique gift to translate these feelings into a sound that got into the heart of the listener.

From there, the pair went on to create a symbiotic partnership: Wild at Heart (1990), Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), Lost Highway (1997), The Straight Story (1999), and Mulholland Drive (2001) were all scored by Badalamenti. Sometimes the music itself would generate a character. Sometimes the composer would hang out on set and play music live to generate a mood for the actors to react. This is highly unusual for the usual Hollywood production, but these contributions gave an authenticity to David Lynch’s films that are still unparalleled.

“David’s visuals are very influenced by the music,” Badalamenti once remarked. “The tempo of music helps him set the tempo of the actors and their dialogue and how they move. He would sit next to me at a keyboard describing what he was thinking as I would improvise the score. Almost all of Twin Peaks was written without me seeing a single frame, at least in the pilot.” His niece Frances interviewed him for The Believer magazine, recalling being drawn to film noir in his youth. “The haunting sounds have been there, the off-center instrumentals, ever since I was a child,” he said. Perhaps Lynch gave him the rod to reel in that big fish, in the proverbial pond of the imagination.

“I sit with Angelo and talk to him about a scene and he begins to play those words on the piano,” Lynch told The New York Times. “Sometimes we would even get together and make stuff up on the piano, and before you know it that leads to the idea for a scene or a character…When we started working together, we had an instant kind of a rapport — me not knowing anything about music but real interested in mood and sound effects. I realized a lot of things about sound effects and music working with Angelo, how close they are to one another.”

The “Twin Peaks Theme” won a Grammy for pop instrumental performance.

In addition to working with David Lynch, his roster of collaborators was staggering: David Bowie. Marianne Faithfull. Orbital. Liza Minnelli. Roberta Flack. Anthrax. Paul McCartney. Dolores O’Riordan. LL Cool J…even a country song with, of all people, Norman Mailer. He composed other music for TV, including Profiler and Inside The Actors Studio, as well as the 1992 Summer Olympics. Several years before Twin Peaks aired, Badalamenti arranged the orchestration for Pet Shop Boys on “It Couldn’t Happen Here.” You immediately hear his signature melancholy synths on the piece, as if bringing Neil and Chris into the same eerie liminal space of the proverbial Red Room…which did not yet exist at the time.

Badalamenti, Lynch and Julee Cruise collaborated on two albums, 1989’s Floating Into the Night; The Voice of Love, and a 1990 avant-garde concert piece called Industrial Symphony No. 1, which featured Wild at Heart stars Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern. He and Lynch also recorded a jazz album, Thought Gang, in the early ’90s. He worked on the scores for Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors and National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation.

In 1996, he worked with Tim Booth, the lead singer of James on Booth and the Bad Angel. “Tonight I will raise my glass to my beautiful friend, the Bad Angel, Angelo Badalamenti,” he tweeted. “He taught me many things but primarily how to enjoy the recording process. We laughed from the beginning to the end of the record we made together, never had a disagreement. I love him.”

David Lynch told the L.A. Times in 1990, “Some of the happiest moments I’ve ever had have been working with Angelo. He’s got a big heart, and he allowed me to come into his world and get involved with music. Today, on his daily weather report Monday, he simply said, “No music today.”

Where he is, now “the birds sing a pretty song….and there’s always music in the air.” Tonight, as we drift off to sleep, let us all sit with Angelo one last time in the Red Room, clutching overflowing cups of molasses-thick coffee, and send him edutitarg tsepeed ruo.

Or via:

Or via: