I step from room to room to find a home,

Room to room to find a home,

Pack my things, be alone.

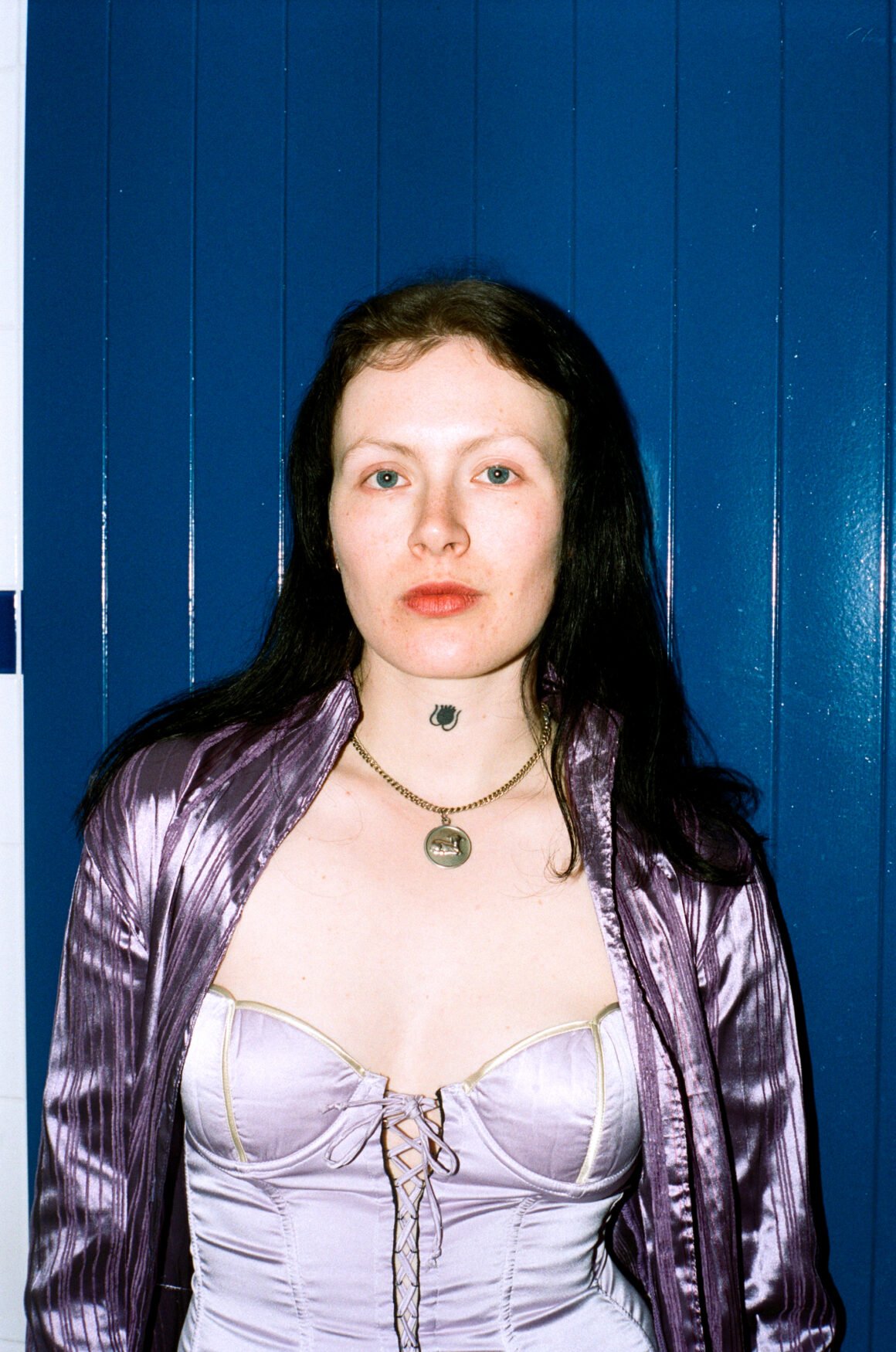

Berlin-born musician and artist Rosa Anschütz returns with Sabbatical—her most post-punk and poetically gothic work to date, and a true homecoming to the city that shaped her. It dwells in the same quiet, mysterious light once found on The Cure’s Seventeen Seconds or Joy Division’s Closer, in the otherworldly drift of The Durutti Column and Dead Can Dance, the devotional austerity of Nico and Current 93, and the raw, ritualistic pulse of Berlin’s own Malaria! Yet its world is entirely her own—defined not by any particular influence but by her sense of cinematic atmosphere. Each song feels sculpted from air and silence, steeped in the sound of memory. Sabbatical is an album that smells of stone and wood and concrete, of grass still wet from morning, and the cooling breath of dusk. It has temperature: cold mornings that sharpen thought, warm evenings that dissolve it. Anschütz bends time through tone, building a cinematic sense of space where emotion takes physical form.

Written between Berlin and Vienna, where she studied fine art, the album gathers nearly a decade of moments—letters to her past self, fragments of light and distance stitched into sound. Released through Heartworm Press, it reflects the trust and exchange between Anschütz and label owners Amy Lee and Wesley Eisold of Cold Cave. Throughout its fourterrn tracks, her voice hovers between invocation and reflection, tracing myth, the feminine, and the subtle ache of return.

Rosa Anschütz spoke with Post-Punk.com about returning to Berlin, creating emotional architecture through sound, and how distance reshaped her understanding of art, time, and herself.

Why the title Sabbatical? What, specifically, did you step away from – and what did that pause make possible creatively?

Sabbatical is very intertwined with my relationship to Berlin, the past of growing up in the city, and my return in 2021, after having lived in Vienna for five years to study fine arts. Sabbaticalwas picking up the thread of guitar-based jams recorded in front of the camera of the Photo Booth, which were early on my first edited music videos.

This album was “a decade in the making.” What survived unchanged from the earliest sketches, and what only revealed itself in the final stretch?

I survived myself by defining the music that I genuinely want to make or feel at a particular time. I can speak about my work as being chained to my life in the way that the poems, which are the ground of the tracks, are all picked up from different experiences. There is something about writing that I would describe as understanding one’s life in a story or poem form; sometimes it can also manifest certain beliefs or morals. A lot of that is in Sabbatical, and for me, it was therefore also an exploration of my own identity and how I have changed, and also how I have not changed in that decade of making the record.

Compared to your previous work, what was the catalyst for the shift in overall sound on Sabbatical?

I am very certain that my album production is primarily influenced by emotion, rather than the instruments. I think perhaps the most significant difference was a cinematic element, which I wanted to emphasize, stemming from my first two film composer jobs last year.

The press materials cite Moon Pix–era Cat Power, Nico, Björk, and Dead Can Dance as reference points for the album’s sound. We also hear shades of Nick Cave via Current 93, Joy Division, PJ Harvey, and David Lynch through Julee Cruise and Angelo Badalamenti. Do any of these references ring true for you—and which influences aren’t obvious but loom large?

The ghosts of all these musicians are certainly there. Press texts are yet another thing, and something as a text that I myself rarely pay attention to. I carry great respect for other artists’ work, but I have never understood the practice of comparing them to each other. If music is written from someone’s point of view, that is such a unique and singular field. For Sabbatical, I had one spirit artist, who is the Metal Queen Doro Pesch. I mean spirit, by her appearance, her looks, but not the music or her lyrics.

Sabbatical is the closest work I’ve heard in a while to the feel of Nico’s The Marble Index, which many consider the first truly “Gothic” album. Did that record inspire you while writing Sabbatical?

I am very fond of all her albums, because they feel like they have been lived. I think this dedication to her work grew even stronger after reading the biography on her, “You Are Beautiful and You Are Alone,“ by Jennifer Otter Bickerdike. With such biopics, they will always carry some colour of the author, but at least they portrayed her bravery and strength, and the unconditional dedication to the arts even through those dark years that she must have been in. The Marble Index did not particularly inspire me, but her work in general was much bigger influence on the record before Sabbatical, called Interior.

This is your first international release outside Germany, via Heartworm Press. Why was Heartworm the right home, and how did their editorial and visual ethos shape the project?

I have become a Heartworm, with the amount of engagement and exchange that was and still is happening with Amy Lee and Wesley Eisold of the label. The way we have spoken to each other made me feel that my work is being understood, seen, and valued. That is really the first time I’ve had such a genuine experience.

Is Sabbatical your first release with Heartworm Press? How did that relationship begin, and what drew you to collaborate with a label known for its singular artistic identity and cult following?

I only know that at some point, my radio show, Total Care, which I have been doing now for over five years, was listened to while they were touring as Cold Cave. On that radio show, I read poems, books, and play my favorite music and field recordings. The first request came through my poetry; they asked for a contribution for the Reader, which they produce.

How did you design the album’s sense of space and silence?

I wanted to build a journey, with breaks and perhaps some of the lyrics having space to continue echoing in it. Some of the topics in Sabbatical were quite heavy and very upfront for me, and I wanted to incorporate them appropriately, also including moments of silence.

What’s the core instrument palette on this record?

My bass, which I bought secondhand in Japan in 2017, was built the same year I was born; my guitar, some modules, and the piano at the house where I grew up.

Can you walk us through how one track on the album evolved—from initial idea to mastering, or perhaps even into its music video?

Some of those images for the videos…I carried it around with me for a long time. Those images come like flashes and are so insistent. So, to take this track as an example, I got the dice, a prop of the video, perhaps 4 years ago, and knew I wanted to somehow swim with them in the lake in front of our house. It only happened in June this summer, when my then-partner helped me film those images. The processes happened at very different times, which made the time until the release be a bit more lighter, because I was involved with the record until the end of July, though the Masters were done by Wesley in February, maybe, and some songs were 10 years old.:)

Who were your closest collaborators on the album, and what did each bring that you couldn’t have achieved alone?

Since the release of my first EP, Rigid, I have worked with Jan Wagner as my co-producer, who is also a very close and trusted friend of mine. Additionally, we asked Kevin Kuhn to contribute to the drums, given his character that colors the way he plays. In the process, my friends were also extremely important, to name my friend Anna Breit, who has shot all the press and cover photos with me, just not this time, the Cover—Agatha Smith, who also guided me through some moments of uncertainty. Additionally, my then-partner, Liam Andrews, who assisted me with filming the videos, primarily during a residency I participated in in March, which was located in Spain.

The lyrics are described as “prophetic and personal.” Where do those two threads meet for you—and what’s a line that changed meaning over time?

In some ways, they are personal, but by deciding to make them a public work, they also lose that quality and perhaps transform into something prophetic. I think this interpretation might stem from the repetition of certain phrases in my lyrics.

“Eva” opens the album with a sense of rebirth and confrontation. Many of the songs explore ideas of womanhood, temptation, guilt, and liberation. How consciously were you working with feminine archetypes or mythic imagery when writing Sabbatical? Do these figures—like Eva or the “demon brothers”—serve as self-reflection, or as symbolic voices that speak through you?

That would be the only track on the album that is consciously feminine-coded, taking this name as a beginning, and introducing another protagonist at the front to dive into the rest of the album’s imagery…I think this track deals more with a certain repression that I have experienced growing up, gendered as a woman. The feeling that you are entering so many rooms, in which you will have things projected on you. That makes you learn to keep things to yourself, because society shows you that your voice will either be unheard, misbelieved, or taken as a threat to an existing power structure. I put the track at the beginning, more like a mantra. Enough, I will open my mouth wide and let all these past and present issues finally leave me. That is also why I called the album Sabbatical.

Beyond “Eva,” several songs on Sabbatical hint at stories of chance, ritual, and letting go. Can you tell us about any other specific mythologies or narrative frameworks you used across the album?

Burlap was inspired by a Noir cinematic touch, a mysterious phone call, a confession of a murder, followed by the track Sun Tavern, which is a sapphic Love song but also written in the realm of a murder ballad. Then there are songs about friendship, trust, like in Swan Song. It might be more like an interplay between the lived real narrative and something more fictional, which is perhaps relatable when you reflect on your own life as a movie or narrate certain phases of yourself, also as a character.

Some tracks on Sabbatical revisit older material that you reworked over time. In doing so, how did you negotiate the original myth or story you had in mind with the person you are now?

Through this interplay of lived real narrative and the fictional, mythical.

You’ve referenced chance, ritual, identity, and letting go as recurring motifs. Several songs feel like rites of passage or transformations of power. Can you walk us through one less obvious track (not “Eva”) and explain its symbolic lineage?

Some recurring themes are also the experience of addiction, which could be traced in Plaster Copy or Poppies in Limelight. These tracks are tainted by a past of mine, that I have worked on to let it not dominate my identity.

Sabbatical alternates between extended melodic pieces, such as “Double Cross” or “Sun Tavern,” and brief, poetic interludes, like “Burlap” and “Tacheles.” How intentional was this variation in song length and structure? Were the shorter tracks conceived as fragments or complete statements in miniature? And does “Tacheles”—with its All the Pretty Little Horses lullaby feel—reflect anything of Berlin’s cultural landscape?

Yes, Tacheles is indeed a reflection on Berlin, as a shaping and changing city, also by the experience of change, once you have left the city for some time and come back. Memory is interesting in that regard, that it needs the environment to exist within it. Moving places is almost like an hourglass; after a certain time, you will forget the street names, some places, and small details, so change becomes a very stark thing, and that was the case when I moved back. The shorter tracks were the connection between those yearly differences of the songs.

The video for “Chase Pioneers” shows you running laps on a sports field at night, face glowing under the floodlights as horns rise and fall around your voice. “Like Oxblood,” by contrast, centers on a solitary piano dirge filmed beneath an underpass at twilight, with tree branches overhead and moth-like insects drifting through the frame. Did you compose these songs with those visuals in mind—or did the music inspire the imagery?

Both images came to me during my stay in Spain in March this year. I took the phrases of the lyrics and decontextualized them in the environment I was in at that moment. I wanted the imagery to become a natural journey by itself, with some things planned but also trusting in the faith of artistic purpose.

The Sabbatical cover (also featured in the video for “Watch Me Disappear”) feels deeply personal yet unmistakably Berlin—everyday objects, a passport photo, keys, lipstick, and a green keychain, reminiscent of something from Berlin Club Memes. Can you tell us about the meaning behind this image and what story it tells about where you are right now?

If you take one Me out of meme we are closer to the simple situation, in which the cover came to me. I had just finished a shoot with my friend Anna Breit and couldn’t decide on any of those beautiful pictures to be the cover. I was so distressed, also to renew my passport that was really due, and I had a gig in the UK with friends, and in that moment of total despair, I looked at my glass table at home, at the exact same arrangement of objects as on the cover, took the video camera into my hand and filmed it. The cover felt fitting because the album was reflecting on my past, and with that passport being renewed, with that one mug shot a new chapter had begun, I liked it also in regard of the Sabbatical. The production and all those years were that Sabbatical. I am at a different point now.

Berlin’s musical history is steeped in post-punk, performance art, and industrial experimentation. Do you feel a connection to that lineage—from Malaria! and Einstürzende Neubauten to the city’s current underground?

I grew up with it, by searching for it. I guess it is a part of me and the city.

Berlin is often shorthand for club culture. How does the city still live inside this quieter record?

That was my teenage years as well, clubs and Techno. However, I think what is even more important is the Goth and Post-Punk environment I found myself in, which was, at that time, 2015, also very close to Techno. Through my past releases, I also played in a few clubs within a club night setting. I am still open to that, another part of me. The city in Sabbatical is living through the way I have perceived it, maybe nobody will relate to that, that’s ok.

How are you translating the album’s intimacy live?

I still have to find that out. I love performance and playing live.

If one song is the album’s thesis, which is it and why?

“There is always a way.“

Looking ahead, are there doors you hope this album opens—artistically, geographically, or in how audiences will be introduced to or understand your work?

I will go to support Cold Cave on their US tour in February, which will be my first time, and also perform the record at various other venues. That is perhaps the first real thing happening, and everything else I can only share, for which I hope for much, but I talk little about it.§

Sabbatical is out now via Heartworm Press. Listen to the album below, and order it here.

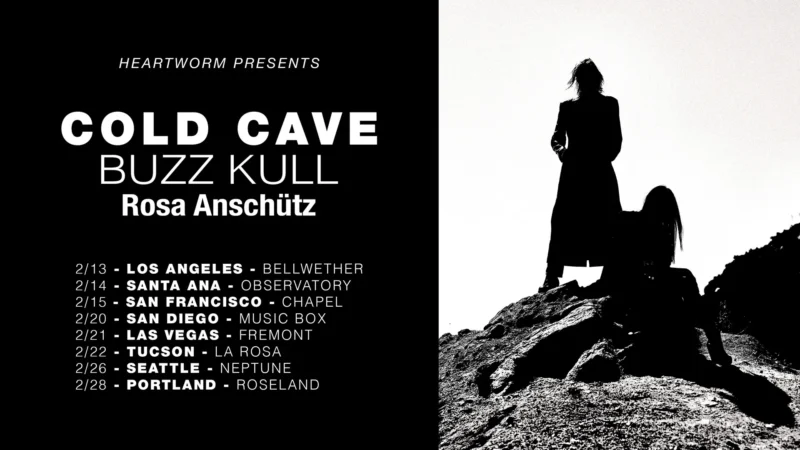

With Sabbatical, Rosa Anschütz enters a new chapter in her career. Beginning in February 2026, she will tour the West Coast with her Heartworm Press label family, joining Cold Cave and Buzz Kull for a series of U.S. dates. The tour marks her first central performances outside Europe and reflects the close creative alliance that shaped the album.

See the full itinerary of dates below.

Cold Cave, on tour with Buzz Kull and Rosa Anschütz:

- Feb 13 Los Angeles, CA — The Bellwether

- Feb 14 Santa Ana, CA — The Observatory

- Feb 15 San Francisco, CA — The Chapel

- Feb 20 San Diego, CA — Music Box

- Feb 21 Las Vegas, NV — Fremont Country Club

- Feb 22 Tucson, AZ — La Rosa

- Feb 26 Seattle, WA — Neptune Theatre

- Feb 28 Portland, OR — Roseland Theater

Follow Rosa Anschütz:

Photos: Anna Breit, Agata Smith and Liam Andrews

Or via:

Or via: