Bob Gaulke, the restless raconteur and poetic provocateur moonlighting from New York City’s classrooms, has long peppered the underground with biting lyrical commentary on class, sex, and alienation. Known for brief but bountiful musical dispatches, Gaulke has already unleashed more than thirty succinct collections into the ether, each a punchy commentary over post-punk rhythms brushed with global hues. His latest venture amplifies ambition, uniting him with avant-pop veterans Shriekback (Barry Andrews, Martyn Barker, Carl Marsh), whose decades-deep careers are marked by rhythmic inventiveness and lyrical sharpness.

This cross-Atlantic collaboration, set to materialize across three distinct volumes: (S)words, (detail), and When Are These Not Difficult Times?, came together through years of digital exchanges and meticulous overdub explorations, deftly mixed by Martin Scian. Initially ignited by a crowdfunding challenge from Shriekback, where fans commissioned bespoke tracks, Gaulke upped the stakes, proposing an expansive multi-track suite. Though that ambitious gesture ultimately shifted form, it sparked a sustained dialogue between Gaulke and Andrews, yielding a series of arresting, genre-fluid songs that reach public ears July 6th, 2025.

“Shriekback have been a part of my musical DNA since 83-84 when I was a teen and first heard “All Lined Up” on college radio in Rochester, NY. Their sense of musical and conceptual adventure seemed to know few boundaries. A song could be made up of a swinging rope or Gregorian chants…but it was always funky. There always seemed to be an active sense of almost scientific exploration going on which kept me listening over the decades. When I saw this opportunity to collaborate with its members in a novel way, I jumped at the chance.”

Gaulke, a public school teacher in the Bronx, has managed to release more than thirty short albums to limited acclaim and audience. He often blends world traditions with a post-punk foundation to achieve a personal fusion of elements. He cites John Hassell and Brian Eno’s concept of “Fourth World Music” as somewhat emblematic of what he hopes to achieve:

“We’re all stuck at home with the world at our fingertips. I think my songs on the template I use sort of reflect that sense,” he says. “I like short songs and albums. After twenty minutes, I sort of get bored. The sessions naturally became albums as I sort of write to a story arc before I pick up a guitar or bass. (S)words (pronounced “swords”) was more guitar-driven. You can hear echoes of old-school post-punk (Big Audio Dynamite, Wire, and Shriekback, natch) in the writing. The songs were written around a sense of lost personal agency with the first trump administration. It seemed like a good moment to finish them up and put out the album.

By contrast, the songs on (detail) were all written on the bass…It was my chance to pretend to be Dave Allen (RIP), who I actually had the pleasure of meeting once or twice when living in Portland. My original plan was to get him playing on these sessions, but things moved in a different direction.”

Both albums feature editing, backing vocals, and guitar work from Dutch singer-song writer, Hans Croon.

“Hans was another teenage hero of mine who’s since become a friend and collaborator,” Gaulke reflects. “We had worked together closely on an earlier project and his work as a co-producer was really important when trying to make sense of a galaxy of overdubs and crazy ideas….And the secret sauce is the Brazilian rhythm section of Gil Olivera (Lucas Santtana) and Paulo LePetit (Tom Ze). Then know how to move a groove.”

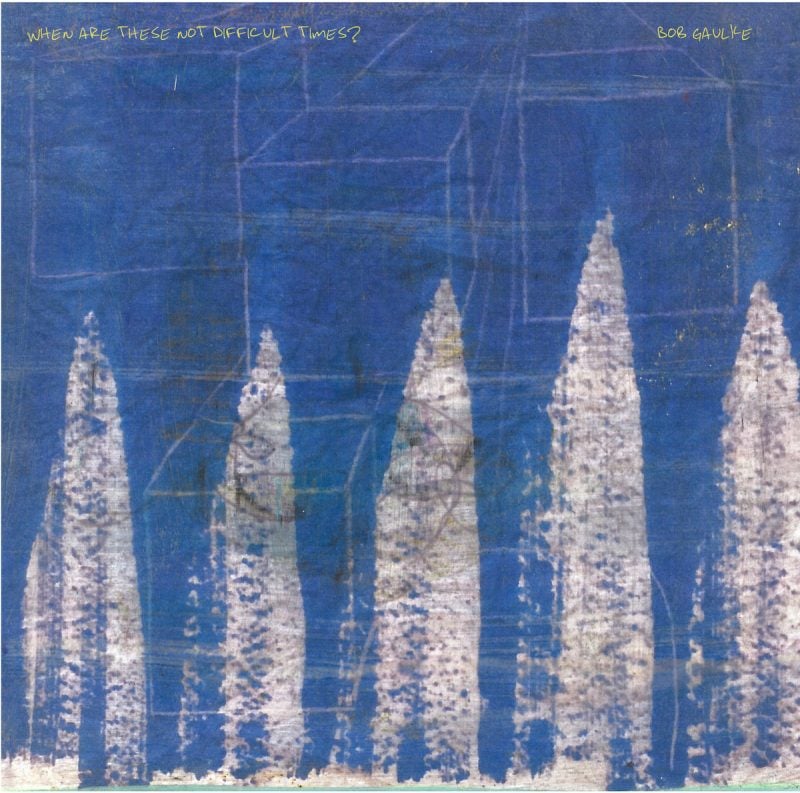

Completing the triptych is the 4-track EP, When Are These Not Difficult Times?… shorter format; a bit more reflective songwriting and different subjects.

“…A bit of a chaser after the two main courses,” he says.

Gaulke plans to be active in the NYC area this summer playing from his catalogue with Leon Gruenbaum (Keyboards) and Gil Oliveira (drums). Gaulke caught up with Post-Punk.com to talk about his creative process, his influences, and work-life balance:

Your creative output has been astonishingly prolific – at one point you were releasing new albums or EPs almost every month. What does your songwriting process look like when you’re working at such a relentless pace? How do you keep yourself inspired and avoid creative burnout while producing so much material?

I had a boring upper-middle class youth so I sort of stick myself into interesting situations and report from there. It keeps the muse happy. In terms of burnout, as I do not have any sort of learned background, I try to incorporate learning into what I do; whether it’s trying chord inversions, writing on top of exotic rhythm loops, or incorporating ideas from new things I’ve read. I guess I write with one eye towards pleasing myself. It was harder to do when I first started, but now I can stand listening back to my own material. There’s something really inspiring about a new set of chord changes or a funky bass line. I continue to listen to new music, experience life, then report back with an album.

Much of your recent recording has been done remotely, with tracks assembled by passing Logic sessions back and forth between collaborators in London, New York, Amsterdam, and even Patagonia. How has this far-flung, file-sharing recording process influenced the sound of your music? Do you find that working in a “vacuum” in the Bronx while collaborating globally presents any unique challenges or surprises in the way your songs come together?

Yes, it’s unfortunate; there are definite drawbacks to the remote approach; the music doesn’t always breathe correctly and there’s a danger in losing dynamics and feel, but it’s somewhat of a way that I can afford to work. I work with people who’ve influenced me, and as you probably can guess, no one’s making a living in the arts. As a single dude with a stable job I guess I do my part in supporting a circle of other artists.

The vacuum is somewhat helpful in that an artist needs peace of mind. The hipsters haven’t colonized the Bronx yet, so it’s an open canvas. Isolation isn’t the best for my psyche, though, as the downside is living a bit like an anthropologist. For this reason, I’ll be focusing more on playing live in the coming months. Cultural isolation is something I’ve done since my thirties when I moved around the world teaching English and I guess that approach stays with me in the jungle of NYC.

In terms of the sound, I’m trying to synthesize these diverse elements into a coherent whole so I guess I’m doing a bit what John Hassell and Brian Eno predicted about future music being this fusion of technology and world cultures (“4th World Music”). I’ve been listening to a lot of Yusef Lateef, Francis Bebey, and Egberto Gismonti recently and these folks created their own homespun, immaculate fusions.

You’ve mentioned that you approach songwriting like a film director, following the “Cassavetes template” where 90% of the work is in casting the right people. Can you expand on how collaboration factors into your writing and recording? When you send out the “bones” of a song to your collaborators, what are you looking for them to bring to it, and how do their contributions shape the final piece?

My own skill set is quite basic; I could always do better with my vocal melodies, I’m sure, but essentially i’ll send out a lyric sung over a set of chord changes, or bass lines, and a rhythm loop. A sketch that needs to be painted over. The chords sequences I usually find interesting; they have to provoke a lyric or match with one that’s moving in the same tonal and emotional direction. What I lack for in technique, I make up for with context. I was lucky in having some brilliant record store mentors and I think what I’ve listened to provides a sense of what’s possible. So it’s this triangulation between what I’ve heard, what I’ve experienced, and what I can play.

I think John Lurie works in the this same way, both with music and painting, where he teases out a scribble and then shapes it into something a little more recognizable. In many cases, I’m providing the scaffolding; I’m the most musically useless part of the collaboration; I just chose people whose work I admire and have them do the coloring. I’m happiest when I’m completely surprised; it’s Christmas in the inbox. If it’s tonally not what I’ve had in mind, I then go back and make adjustments to the lyrics to match.

Your music has been described as an eclectic blend that “dances on the fence” between pop, rock, psychedelia, jazz, world music, and dub reggae – and it’s notably rooted in Brazilian Tropicália and soulful post-punk influencesd. What draws you to such a wide palette of genres? When you’re writing a song, how do you decide which stylistic elements to incorporate, and how do you ensure these diverse influences coalesce into a cohesive sound that is distinctly you?

Well, I grew up with the first generation of MTV and college music and as Daniel Levitin has written in This Is Your Brain On Music, the music of your adolescence is tattooed on your mind as some sort of starting point. In my case, that was post-punk (Heaven 17, Fun Boy Three, Scritti Politti still get props). However, particularly as one starts writing, one’s tastes change. And life experience changes a person as well.

I don’t make Brazilian music, but I’m inspired by the palette. If chords have particular emotional resonances, one needs a different palette to color different experiences at different ages. Georges Moustaki once said, “Every decent song starts with emotional truth”. I’m looking to be true to the emotion I want to convey. I mean, as gringos, we don’t put that emotionality into our daily lives. We have to stick into our arts or we get locked up for being too passionate or violent.

In terms of cohesion, the diverse elements have to support the meaning/intention of the song. I don’t think consciously of style; I just want to make something interesting to myself and expand my limited skill set. That being said, I’m drawn to the feeling of physical liberation from cultures that produce a type of “body music.”

You grew up on the first wave of post-punk and admire artists like John Cale, Ryuichi Sakamoto, and Caetano Veloso. How have those formative influences – from the art-rock experimentation of someone like Cale to the Brazilian Tropicália of Veloso – shaped your approach to songwriting and arranging? Can you give an example of a song or album of yours where you feel these influences really shine through in the music or lyrics?

These artists I mentioned I cited because they are/were fearless in their innovation. I feel you’re either an idiot savant/beautiful dead loser, or you’re a scientist. I don’t think there’s room for much else. My father was a classical musician, so I’m sure the rigor of that approach is what attracted me to Cale and Sakamoto. My mother was Iranian. Iranians shit poetry for breakfast, so that’s basically how I see myself: A half-poet born into a half-musical family.

I don’t know if I’ve stolen anything in particular from any of these dudes, but with Caetano, at times in his work, he’s only suspended by the strength of his ideas; he doesn’t really possess a musical virtuosity. Cale is a bit more interesting in terms of how much he was a creative compliment to Lou Reed and how emotionally repressed he was coming from a European classical background. I feel his best work is when he loses his mind, lol, amidst all his technical brilliance. Sakomoto was just fearless; a scientist of sound. And with Sakamoto, there’s the dream of the piano. I dream of not dying before I can get decent on the piano. I really can barely play my instruments. It doesn’t stop me from buying more of them, though.

Let’s talk about your three latest releases – the two albums (S)words and (detail), and the new EP When Are These Not Difficult Times?. You described the EP as a “coda” to the first two albums, perhaps marking a different direction from them. What themes or musical ideas were you exploring across these records? Do you see them as interconnected pieces of a larger narrative or concept, or does each have its own distinct identity and mood in your catalog?

I feel so much of creativity is organization; where do the ideas fit? How big are they? I think in terms of albums being a story. I don’t always remember the circumstances that inspired a lyric but in essence I’m trying to convey a sense of life from behind my eyes from the minutiae to the dreaming. Hopefully, if I’m doing this correctly, I have kept track of things I’ve previously written about and am not duplicating myself, but inevitably individuals are limited in scope, so themes carry over.

(S)words is meant to be aggressive; a sense of waking up into a world that should be so much better; a world that was promised and stolen by theft and greed. I mean, historically, I span from the Seventies until today, so I’ve felt the social damage done to the promise of a middle-class society taken apart through oligarchic policy. How are those big ideas felt in a little life? In a society that is soaked in all sorts of violence; directed towards itself and the world. That said, I’m an optimist, but I think we feel everything. I teach public schools; I see it behind the eyes of students seeming to say, “Is this all there is?”

(detail) is many ways is the flip side to (S)words; more nocturnal/internal; hopefully the humor is a bit more on the surface. Perhaps it’s more of a feminine take on the same themes? All the songs were written on bass, so that probably tilts things in a more “open”-feeling direction.

When Are These Not Difficult Times? notably features a collaboration with members of Shriekback – Barry Andrews on keyboards and Martyn Barker on drums. How did this collaboration with such legendary post-punk musicians come about? What was it like working with artists from a band as influential as Shriekback, and did their presence influence the sound or creative process of that EP in any unexpected ways?

…I was a huge fan of Shriekback’s early work; I got into them just before Jam Science and it was amazing to me coming from being an XTC fan that Barry was the same guy in both projects. As you probably know, the band has been ahead of the curve in terms of crowdfunding and fan outreach. At a certain point about a decade ago, they offered to commission a piece of music for keeps, then later changed the policy. I squawked to them loudly about this so we worked something out where they would play on my work in exchange for me granting them permission to use my commissioned pieces.

Other coincidences abounded as I had already met Dave Allen on two occasions while living in Portland and subsequently met and have worked a bit with Ivan Julian here in NYC. I’ve got a lot more with the Shriekback gang in the pipeline. In terms of sound, Barry just fucking delivers. Never predictable. And one just tries to survive the impact, lol. Martyn’s a bit more adaptable. I wrote these songs knowing I’d be working with some of my idols; I think their idea DNA is already in me, so perhaps they recognized a distant nephew.

In addition to Shriekback, you’ve worked with an array of international artists like Dutch guitarist Hans Croon and Brazilian drummer Gil Oliveira on your projects. What do these cross-cultural collaborations bring to your music? Can you share how collaborating with musicians from different backgrounds (geographically and stylistically) has enriched your songwriting or challenged you to approach music in new ways?

Gil’s drumming is a bit like Barry’s keyboards. He can play anything and it’s always interesting. I’ve had engineers just have their minds blown when lays a groove down. So he comes in and replaces the loops and that goes a little way to returning some dynamics into the arrangement. Hans did the editing and added his guitar and backing vocals. I think that was a good match for his skill set. I don’t want to invoke national stereotypes, but he’s Dutch, lol., from a great band called The Dutch, which has continued since the 80’s in crafting perfect pop. I have no objectivity about how things are sounding so I rely on someone like Hans to bring things together. Barry sent millions of keyboards over so Hans went through the overdubs and figured out what worked. I think our approach is quite seamless on (detail) in particular.

Many of your songs grapple with themes of class, sex, alienation, and political undercurrents in modern life. You’re not afraid to write about uncomfortable realities – from critiques of economic inequality to intimate social observations. What draws you to these subjects as a songwriter? Do you see your music as a form of social commentary or storytelling about the world around you? In tackling such complex themes, how do you balance being pointed or provocative with being poetic and open to interpretation?

A lot of this does come from the Post-Punk background; how can one listen to Gang of Four and not see things differently? I never thought my boring life was interesting enough, but once you start moving around the world and gaining experience, you start to see some social patterns. I’m amazed at how many people namecheck groups like GO4 or Scritti and write endless drivel about their romantic states. It almost feels like a conspiracy at times. I don’t know how people interpret or misinterpret my work. I’m not that well-known enough to get much feedback. Perhaps music today is the only safe space left for our fragile emotional states, but the lack of social commentary in so much of pop in these dangerous times is dangerous in of itself.

Alongside being a musician, you’re also a veteran school teacher in the Bronx, teaching English language learners in one of New York’s poorest neighborhoods. How has your teaching background and daily life in the classroom influenced your music? Do experiences from your day job ever find their way into your lyrics or the way you think about making music (for example, insights into communication, empathy, or the struggles your students face)?

I steal all my ideas from them, lol. Adolescence is the start of your adult life. I try to get over the cringe moments and try to get a feel from what they’re going through. I don’t even think many of them realize what a disadvantage they’re starting from; they just consume social media and buy Nikes like the rest of the nation. What they’re lacking is what many Americans are; beyond the social connections, the low literacy is the hill I die on. I buy books for kids just to hip them to stuff. If we start with comic books, then that’s where we start. They definitely color my writing. I think Paul Simon said once, “Three implies direction”. Ideas start to percolate and I write them out. It somewhat therapeutic for a stress I willingly put myself through.

On a practical level, how do you balance a full-time career in education with a prolific music career? Since 2005 you’ve been working as a teacher by day and steadily releasing albums on your own time. Has maintaining that dual life changed your perspective on what success in music means? Do you find freedom in not having to rely on music for income, allowing you to take more artistic risks or follow your muse more freely?

I balance things out by crying a lot. I met many of my heroes on a recent trip to Rio and to a person, they all married rich and had significant side hustles. I didn’t start doing bands until I was 27-I think I’m a late bloomer. I never feel like I’m wasting my time helping poor kids, but of course I dream of my work finding even a small audience one day. It can be very painful; I was warned, though.

Your album The Humanities was very much a product of observing life in the Bronx and New York City – you wrote as a “former middle-class gringo” watching people “lurch from crisis to crisis” in a 21st-century urban landscape. How does the environment of NYC, and the Bronx in particular, seep into your songwriting? Are there specific songs you’ve written that you consider portraits of your neighborhood or commentaries on city life? How important is setting and a sense of place in your music?

Well, I don’t feel that what going on in the Boogiedown (Bronx) is that removed from the rest of America. Perhaps we’re five minutes into the future. A huge change in American life has been the effects of changing immigration quotas on demographics. In this regard, the Bronx is somewhat representative of the US. I tell my kids (majority Dominican/Latino) that they’re the new White people.

I wouldn’t be considered White a hundred years ago. This point is often lost in the political dialogue. My job as a public school teacher is to make new Americans. And I try to do that, unironically. I remember seeing black goths in Bahia. They were beautiful. Who would’ve thought that Morrissey would have a huge Mexican fanbase? We should all be about the flavor. I remember talking to a reporter who went undercover with white supremacists in the NorthWest. The kids eventually tired of waffles and baseball; that’s when they stopped being nazis. I truly believe in strength through diversity. We all grew up on Star Trek and Sesame Street, didn’t we? Setting and characters are all important. Again, as a writer, my hardships can be turned into gold. When I step out of my apartment, my mental recorder is always on.

You’ve lived and worked in far-flung places like France, Japan, and Brazil during your journey as both an educator and musician. How have those international experiences – learning languages, immersing in other cultures – impacted your music? For instance, did your time in Brazil studying Tropicália or in Japan and France broaden your musical vocabulary or the topics you write about? In what ways has being a self-described “rootless cosmopolitan” shaped your identity as an artist?

I think we should all take what’s best from the world and ignore the rest. Speaking a second language slightly shifts your personality. Being a fish-out-of water sharpens your powers of observation. So much of learning is just exposure-I don’t think that should change as an adult. My heroes are the people who are always learning, reading, and traveling.

A signal event that blew my mind recently was a 5-hour dinner I had with Judy Nylon. She’s 78 and still involved in fashion, rock, politics, and culture. She gave me her benediction for my work and I hope one day to grow up to be like her. I think at its best, this is what the Post-Punk experience was alluding to; culture clashes; whether it be reggae and rock (Clash) or disco and punk (ZE Records) or whatever Malcolm McLaren was onto next. At the heart of creativity is sharing freely. That’s what informs my growth.

France has a strong troubadour tradition (the poet who sets their verse to music) in Chanson; Brazilian music is like an alternative universe of information that richly informs how I write. It comes from listening critically to new songs; taking listening as a form of learning and hopefully meeting people who guide you through the experience. Taking it all home and trying to make it your own. Someone said that both Brazil and Japan are post-modern societies with the ancient sitting side by side with the future. Japan, culturally, was definitely one of the toughest things I did. I forget all the hardships and get ready for the next adventure. Lately, I’ve been thinking how we’re all our own cultures onto ourselves. I hope the signal I’m broadcasting has some resonance and coherence.

There’s a streak of wry humour and satire in your work, even when dealing with serious themes. On The Humanities, for example, you have songs narrated as an AI from Uber Eats, or about “sex with hedge funders” and “sex with social workers,” which mix absurdity with social commentary. How important is humor and irony in your songwriting? Do you find that using a bit of absurdism or dark comedy helps you address difficult societal issues more effectively? Can you talk about how you balance the tongue-in-cheek elements with the earnest messages in your music?

Again, I think emotionality is the coin of the realm. The heart beats the head every time, so I don’t want to appear too detached and ironic. Do you know the tune by Herman Brood, Never Be Clever? I occasionally slip things in but I hope I’m conveying something emotionally resonant that I’m concerned about. Eventually, you have to choose life, I think. You see what works and what doesn’t, but constant cynicism starts to burn you out. That’s why a lot of people can’t do Steely Dan. The heart doesn’t have a lot of parking spots open for the snide. I think songs can make us feel less alone. I wrote a song about Andy Partridge in a sincere attempt to cheer him up.

In terms of production, you’ve experimented with a “less is more” approach. I recall you mentioning that on one record you employed dub-inspired principles – “when in doubt, leave it out” – to keep arrangements sparse and effective. What is your general philosophy in the studio when arranging songs? How do you decide when a track needs additional layers and experimentation, versus when to strip things back to a minimalist core? Are there specific albums or songs where you challenged yourself to keep it simple, and what did you learn from that process?

Yeah, the song has to be served. I think I’ve gotten pretty indulgent with some albums; I’m playing with some world-class musicians. I try to mix things up and strip things back. And there’s always the nightmare of my older brother pointing out to me that I really can’t play my instruments. So, I’m playing live from here on out, just to remind myself that I exist. My parents are both dead and I just lost a best friend. There’s a weird bonus in getting older in that you start to care less about what other people think, particularly when the important people in your life have gone.

Lyrics and poetry clearly play a central role in your music. You’ve been praised for your expressive, witty lyrics – one reviewer called you an “un-drunk existentialist Bukowski” in terms of writing style. How do you typically approach lyric-writing? Do you carry notebooks of poetry and later fit lines to music, or do the words and melody develop together organically? Also, who are some of your literary or lyrical influences – are there poets or songwriters whose work has inspired the way you craft your lyrics?

Yeah; I write lyrics first, which gets me in trouble with vocal melodies. I took a workshop twice with Martin Briley where he emphasized that for US/UK pop songs, the vocal melody is king. I used to carry notebooks, but now I write on my phone. I then have to go fishing for chord changes that match the emotional contours of the lyric. It’s a bit like ceramics, if you follow the metaphor; you’re squaring the words against the chords; sound vs sense and then tweaking both to make a fit. In terms of influences, I just read; I’ve always read. I read whatever interests me. I guess it goes back to childhood where heaven felt like a big stack from the library, my air conditioner, and chocolate chip cookies. I remember feeling really “advanced” reading Richard Brautigan at 14; but that’s the perfect age for that. Brautigan, Vonnegut, Pynchon, and Bukowski all seemed to make feeling grown-up easy.

Being middle class and really into culture presents problems as you get older as so much of it functions as toys for the rich; it stands as a sort of aristocracy we can all join through education; yet some people still gatekeep though; the number of dates that’ve ended badly with comparative lit majors; my literary interests have created a lot for sexual dysfunction in my adult life.

Howard Devoto wrote my life; I found myself living inside of Magazine lyrics as I got older. I guess Andy Partridge initially; Phil Judd of Split Enz; Ian Dury seems to tower over his contemporaries; Green Gartside, as I mentioned; a huge amount of respect for Jerry Dammers and what he created as well as Paul Weller for following his muse with The Style Council and so many others. The Slits and Les Rita Mitsouko. Outside of Post-Punk, I learned French listening to CharlElie Couture albums and Sergio Sampaio’s brilliant vibes forced me to learn Portuguese.

You’ve described yourself as identifying strongly with the troubadour tradition – essentially the poet-with-a-guitar crafting songs as storytelling. In the modern era of music, what does being a “troubadour” mean to you? Do you view your role as a singer-songwriter in a similar way to, say, the folk or protest singers of the past, or the French chanson and Brazilian lyricists you admire? How do you aim to connect with listeners through that storytelling lens, and has that approach evolved over time?

Yeah; I’m interested in narrative/storytelling; that creates certain criteria for how you present the work; you’d like lyrics to be clearly understood, but there’s the larger arrangement to consider. The troubadour has their fingers on the pulse of what’s going on so that sort of implies opening up the subject matter a bit wider than pop usually accommodates. Again, I wish my melodies were sharper; that’s always the hope for the next song. I’m still in the trenches, trying to find a balance of sound vs. sense. I feel I might have gotten there with Heat Sink from The Humanities, but I don’t know if anyone else feels that way. I guess I think of Phil Och’s later work on the West Coast where he was matching all these baroque arrangements against his still-trenchant social observations as a model to follow. Not the suicide bit, though.

You are in the midst of a remarkable creative run – I believe you set out a plan to release as many as 50 albums/EPs and were 15 titles in as of earlier this year. What keeps you motivated to maintain this intense output? Do you have an overarching vision or goal for this large body of work (for example, documenting certain ideas or experimenting with different genres on each release), or are you simply following your inspiration from month to month? And looking forward, where do you see your musical exploration taking you next as you continue this journey?

I write compulsively, just to get through my life. Some of this was intentioned. I certainly continue to do stuff to serve the muse. I’ve got about 50 near-completed albums on my hard drive, but I’m just sort of going with the “new ideas only” credo moving forward. I’m a bit in debt with paying for all this, so we’ll see where things go. I hope there’s some sequence to all of this and I just hope I’m not repeating myself.

As I mentioned, I try to incorporate learning into my aesthetic. I’ve got an idea of where I want to take things in the future; I’d just hope to find a small public. The next thing that’s coming out is a collaboration with Marcos Cunha, a dear friend and a maker of Brazilian soundtracks, and Junior Tostoi, a guitarist who’s a bit like Phil Manzanera meets Reeves Gabrels. I’m just trying to not be blown off my own album.

Over a career that spans decades, you’ve referred to yourself as a “late-bloomer” and a lifelong learner in music. How has your perspective on making music changed from your early days trying to form bands in the ’90s to now, as an independent artist in your 50s? Do you feel that age and experience have given you a different voice or confidence in your songwriting? Additionally, what advantages do you think there are to creating art outside the typical youth-driven hype cycles of the music industry?

I feel fortunate in still being hot while old (joke). Obviously, the tech has made things easier; the tools are amazing, that being said, everything might just mean a bit less. Albums used to be the internet. I hope I’ve got a menopause strategy in place where I can just position my work and don’t have to compete with twenty-year olds for listeners. I can’t compete! But my hope is that there are people who connect with what I’m saying and feeling and that might be enough. I’ve got a friend who writes music for NPR and plays in his trio weekly. His advice? “No one’s coming to save us.” I just hope to continue to do my thing. Ultimately, writing demands experience. When I was younger, I didn’t have the stories. I’ve got ‘em now.

Ironically, it seems that giving up on the idea of “making it” commercially allowed you to truly find your sound – as one article noted, once you shrugged off the pressure to chase mainstream success, you honed a remarkably accessible yet genre-blending style on your own terms. Can you talk about that turning point in your life? How did letting go of industry expectations influence the music you make and your definition of success as an artist? Do you ever feel vindicated that the lack of commercial constraints has opened up more creative freedom and authenticity in your work?

Yeah, I mean I was ambitious; when I was 20, I did a school year in France with a pocketful of addresses of musicians I had listened to. The Nits in Holland made an impression as here was for all intents and purposes, a group of middle-class artists making creative pop on a major label. That clicked with the professionalism I knew as the son of a classical musician. The problem was, I couldn’t play or write yet.

I connected with a fellow malcontent a few years later when I was back home in Rochester, NY. And we did bands; he was sex/drugs/rock’n’roll and I was thinking I could do this as a career. Anyways, there are hundreds of discreet skills that need to be learned in this field and some people are fortunate to launch something out of university where there’s a structure to support you. We were a bit late for that and so never really got traction (There’s also the rule of nostalgia that works in twenty-year intervals. We were doing a post-punk sound in the 90’s. Wrong decade for a revival.). So my thirties were about learning those skill-sets and I didn’t get my writing end together until my forties. There are choices and consequences. I’ve spent all my time and money keeping the muse happy and people walk in and walk right back out of your life if you don’t prioritize them. The songs are a sort of consolation, I guess. I currently, just want to be real to the life and experiences I’m having now; at 85 years of age or however old I am. Even the greats at twenty are writing about the problems of twenty-year olds.

“(S)words” feels like a statement of intent right from the title—a play on “swords” and “words.” How did that linguistic duality shape the record thematically? Were you consciously exploring the idea that language can cut as sharply as any blade, and do any tracks on the album most clearly embody that metaphor?

Exactly this. I hope my words cut! I think “Please Rise” is my most Big Audio Dynamite socio-political number on this album.

You’ve said that “(S)words” was largely guitar-driven, while “(detail)” was composed almost entirely on bass, and When Are These Not Difficult Times? serves as a reflective EP “chaser.” What prompted those distinct instrumental starting points, and how did writing on different instruments alter your melodic instincts, song structures, or even lyrical tone across the three releases?

I’m just a very limited guitarist so that probably inspired more simple lyrical moments. I think Martin Gore once said, “life doesn’t happen in major chords”, but rock sounds good with them, so one tries to amp up the hormones a bit on the lyrical side to match.

With bass, I can stretch out a bit more. I had just bought a Squier IV, so that created an interesting sound. The song, “Human Television” on “(detail)” was written on it; I’m consciously trying to be groovy like Dave Allen, but with chords. The Brazilian artist Lenine sometimes plucks his guitar like a bass; the same approach. It seemed to work. The E.P. seemed to have songs of a similar cast and I felt the four songs worked well together and were tonally different from the other 16 tunes that comprise the two albums.

All three projects were mixed by Martin Scian after years of remote overdub sessions. What role did Martin’s mixing play in giving each release its own sonic fingerprint while still tying them together as a loose triptych? Can you point to a specific mix decision—say, a spatial effect, vocal treatment, or rhythm-section balance—that fundamentally transformed a song for you?

I just sort of blindly trust Martin; he’s an A-level mixing engineer based in Patagonia ; an early adapter of Logic. The arrangements were created by myself with the other artists, and as I mentioned, Hans Croon had a big hand in editing them. What would blow me away about Martin’s mixes was the depth and detail of the stereo image he creates on the tracks- he finds a place for everything.

On “(detail)” you’ve mentioned channeling the late Dave Allen’s bass swagger as a tribute to both his Shriekback era and his post-punk legacy. Could you walk us through one track where you most consciously “pretended to be Dave Allen”? And/or what are your favorite basslines of his from Shriekback or Gang of Four?

Re: Dave. Well, I think one wants to create something funky and melodic at the same time. I’m a pretty DIY player. I think Women of Earth or Moving Center might pass muster. For Shriekback, I loved all his work on Jam Science. I only found out years later all the songs were Carl Marsh compositions. The first side of Oil & Gold is completely killer, as well.

The songs on “(S)words” were written amid the first Trump administration and a sense of “lost personal agency.” Looking back now, which lyrics from that record feel most prophetic—or perhaps most cathartic—when you perform them today? Conversely, does When Are These Not Difficult Times? suggest any glimmers of resolution or new questions that grew out of the earlier albums’ political unease?

Well, Please Rise is a call to activism that I hope still sounds relevant ; I think we’re always trying to insert glimmers of hope into what we write; I hope my writing doesn’t come across as too dark. Sometimes there’s this weird mojo where lyrics become predictive; I have no idea where or when inspiration comes; I try to just clean the rust off my antennae and receive the cosmic signals.

Follow Bob Gaulke:

Or via:

Or via: