Peter Hook, who we all know and love as the formidable and influential bassist in post-punk’s history, didn’t let his dramatic 2007 departure from New Order phase him. Since 2010, he’s been touring under the name Peter Hook & the Light, playing Joy Division and New Order albums in their entirety and in sequence from their release dates. This time around, The Light have been playing both New Order and Joy Division Substance compilation albums.

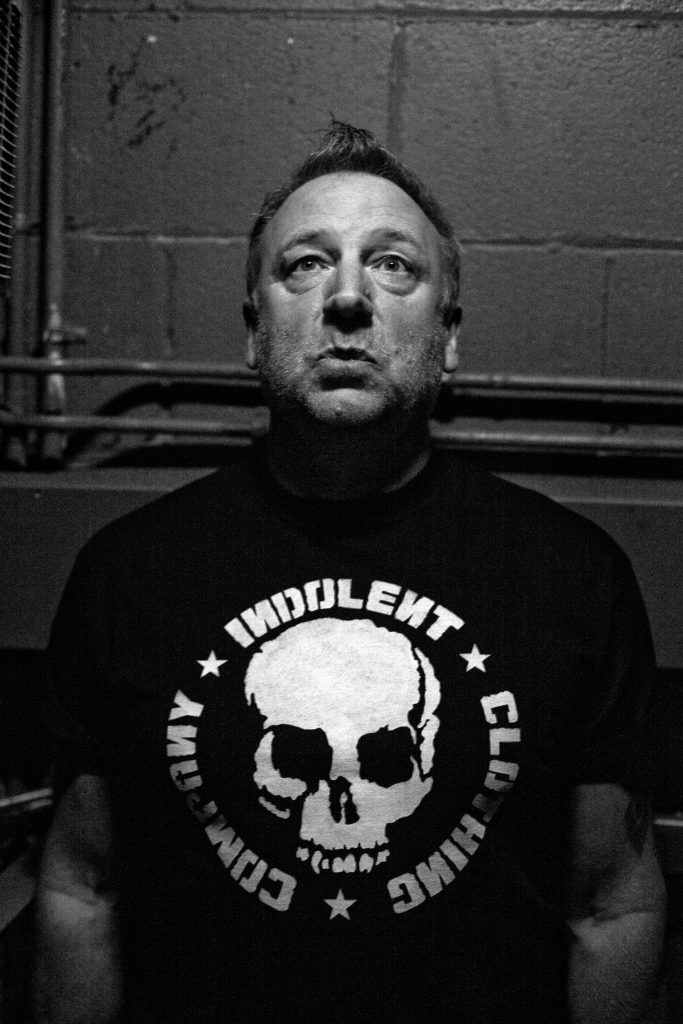

We had a chance to talk to Hooky about the touring with The Light, his new book Substance: Inside New Order, and the infamous Unknown Pleasures album art. All of this—unsurprisingly, as it is Hooky’s specialty—sprinkled with a bit of trash talk. North American tour dates are listed below.

This tour you’re playing both New Order and Joy Division Substance albums in their entirety—what’s the history there?

The New Order album was done specifically by our record company guy [in 1987] because he bought a car with a CD player in it. He decided the first CD he wanted to play in his car was a collection of New Order singles. Our singles had never been released before on LPs, they were always stand-alone. His idea was to collect the 12” singles together and put it out as a record to play in his car. And it was our cheapest album, which was quite interesting, because all the songs were done and they just needed to be put together. When it was released it became our biggest selling album ever. And it sold 2 million on double vinyl in America alone in 1987. Substance made New Order a huge success.

Joy Division’s Substance was done afterwards to mirror it, actually. It was a much different record though. The New Order album is a collection of singles, so they all have a likeness, a poppiness to them—how people usually do singles to make them successful. Joy Division’s is a lot darker. The tracks on it were little-known so it had a completely different feel. It’s quite weird when we play them both together—they feel completely different.

It’s interesting because, in a way, you’re appealing to two different fanbases.

The thing is that I’ve noticed with Joy Division fans—because we started The Light celebrating Joy Division first with Unknown Pleasures, Closer and Still—they are different. When we moved into New Order, we saw different reactions. But the thing I like about playing albums in full is that I like the awkwardness it creates. It feels more arty in the way that they’re difficult. On the New Order LPs there were some songs that we never played live—ever. We deemed them too difficult.

But when The Light came along to play the albums, we had to learn how to play the difficult songs. And we do succeed. I just think groups are pretty lazy when it comes down to it. Playing the albums in full is a delight because they’re long, and I can see people go through phases with tracks they like or tracks they find a bit weird. And I quite like that as a musician—it appeals to me. After years of being in New Order where we played a greatest hits set, it was all about pleasing the audience. It’s actually quite nice to get to [the full album] concept. And I must admit, it makes the band work very hard. You can feel that people have grown to appreciate the difficulty involved in doing what you’re doing.

My idea is to play every record I ever recorded before I join the several musicians in the sky, I’m on album number 7 and 8, so I’ve got a few more to go.

I saw The Light in 2010 with Unknown Pleasures, and then your last tour with the Brotherhood and Low-Life albums. Your shows are always high-energy and fun—I love that awkwardness you talk about, when you play tracks that maybe not everyone knows or appreciates.

It was Bobby Gillespie from Primal Scream that gave me the idea. When he revisited Loaded, the tracks that he liked best were the ones they didn’t usually play because tastes have changed and maybe [the songs] felt newer. That’s exactly what happened when I came to look at Joy Division albums. The tracks we didn’t play a lot… well, all of them we didn’t play a lot, we didn’t play any Joy Division music for 30 years. To get them back was an amazing feat—it felt wonderful.

I always thought that my favorite side of Brotherhood was the acoustic side. Yet, when we came to play the sequencer songs which make up side two, it was those that I loved! I like the fact that side two is a little bit more difficult and different. With New Order in particular, I felt I got into a rut with playing the same set all the time. It was deathly boring—especially with the repertoire we had. I was delighted to see when [the rest of the band] came back as New Order they did exactly the same thing again. My wife always says to me: “Aren’t you glad you’re not there?” And I’m like, “You know what, I am!” It’s richer and more interesting to dig out these little nuggets and go: “Look at this, this is really difficult to play but what a great tune!”

With the fans, when we started out in 2010, there wasn’t a lot of them. We’ve certainly grown a lot in stature as a group because the fans have got to trust what we’re doing. And I can’t thank them enough for it. Having two bands in competition with each other—Peter Hook and the Light and New Order—and to get the accolade that you play New Order stuff better as The Light than New Order do, it’s a wonderful thing!

So what’s next? New Order’s Technique and your other project, Revenge?

Yes! Potsy [David Potts] and I have had many discussions—he plays guitar in The Light and was the guitarist and co-writer in Revenge. He was also my co-writer in Monaco—so we’ve been thinking that.

It’s weird because Technique is my favorite New Order record. I’m really looking forward to playing it. And Republic will benefit greatly from being played in its entirety. When you listen to Republic, it’s very Pet Shop Boys-y, it’s quite camp. We had a bad time making it. The trouble with having a bad time making it, is that it colors you from then on. In the New Order book [Substance: Inside New Order] that’s out in October, I wrote about how it is a good album and there’s some good songs on it. But whenever I listen to it, it always reminds me of something that wasn’t quite comfortable—I wasn’t happy and it doesn’t take me to a happy place. Obviously, a lot of people that listen to it have a completely different feel, which is nice. The Light will do our best to do it justice, without a shadow of a doubt. I think it will sound a lot better.

Since you brought up your upcoming book, I think it’s interesting how you titled it Substance while you are playing the two Substance albums at the very same time.

Originally, when I fell out with New Order, the book was called Power, Corruption and Lies because I was feeling a bit bitter. It’s 800 pages, and that’s cut down from the e-book, which is nearly 1,600 pages. It was too substantial to be called after an album. Maybe i should have called it Substantial, but the book, i think, seems to have a lot of substance.

New Order were a fantastic group and I’m proud of everything we achieved. And I must say that Barney [Sumner] did a real disservice in his book [Chapter and Verse] in the way that he didn’t write about our achievements. He’s done something so wonderful in his career that I couldn’t believe he resisted the temptation to write about the wonderful things he did. Instead, he focused on the shitty things that he accused me of. I didn’t know if to feel flattered or sad in the way he ignored New Order to have a go at me. Out of the 100 pages he devoted to New Order, I think 69 were calling me a bastard. So I will have to take it as a compliment.

I was going to ask if you read Bernard’s book.

Yes, I had to get legal advice and get him to change some of it because most of it was wrong. He had to change quite a lot in the book.

At what moment did you realize what a huge impact Joy Division had on music’s history—not only for post-punk, but for all of it in general?

Since we’ve been playing Joy Division around the world, there’s been a few moments. I thought a lot of these gigs would be full of fat old blokes like me—all bald and old—then we got there and the audience is really young. That actually surprised me. To play in a place like Mexico City and to realize the average age of the audience was about 21, 22, or 23, you’re like “Whoa!” People still resonate with the music—young people especially. Martin Hannett, who was the producer of Joy Division, really did a fantastic job.

And that era of music—Death Cult, Sex Gang Children, Play Dead—it’s quite dark, quite Joy Division-y isn’t it? It’s interesting that people love it today. Great music is timeless, not only for Joy Division but The Doors, Iggy Pop, and Velvet Underground. I’m delighted to say that most bands get compared to Joy Division. If you don’t get compared to Joy Division, then you get compared to New Order. I happened to be in bloody both! I struck it quite lucky there. When you realize we were 21 when we wrote Unknown Pleasures, musically it sounds very mature. It amazes me, actually, how far we’d come from punk, which was just about screaming at everybody and telling everyone to fuck off. To become quite an accomplished musician in order to make an album like Unknown Pleasures, and repeat it again with an album like Closer, I don’t know where that came from. I don’t know whether it was a combination of luck, talent…

Bernard and I, from being old school friends at 11, certainly were very lucky in that it prepared us to stay together and we really accomplished a lot in our chosen field—which was music. Neither of us were a musician until we saw the Sex Pistols at age 20. It seems quite bizarre now to go around the world and see Joy Division everywhere, to get this host of bands that sound like Joy Division: from Interpol to… my god, all these people. It was quite funny when New Order split up, Interpol was advertising for a bass player—I applied and they turned me down.

Really—why?

I don’t know—I applied as Peter Hook. Maybe they thought someone was taking a piss.

What do you think of the mass appropriation of the Unknown Pleasures album art?

Sadly I’ve just gone through this legally. We took it from the Cambridge Encyclopedia, and it’s the chart readout of the [Pulsar] called CP-1919—that’s the graph that it left. All we did, instead of it being black and white, was change it to white on black. The music gave it a completely different significance.

Joy Division are the most bootlegged band in the world from each point of view. There’s a bit of a joke in it, how we sell the most merchandise of any band, yet no money comes to us. If you go on Amazon or Ebay, it’s full of Joy Division bootlegs. Strangely enough, the only time the rest of the band get pissed off with the logo is when I use it. Which I suppose, in a funny way, just about sums it up for them: it’s okay to use it at the end of their show, but it’s not alright for me to use it. The battle is still waging royal between us. It’s an odd one really, because Peter Saville, the designer who did the sleeve, took it from public domain and it should remain that way. Joy Division has the music and that’s the most important thing.

I’ve seen the logo on Mickey Mouse t-shirts, drawn in with cats…

It’s funny that Walt Disney was bootlegging us because they are so careful and so angsty when anyone bootlegs them. That was a funny one—we got to send them a couple nice letters poking fun at Walt Disney because it was definitely a mistake on their part. But I’ve got one! I made sure I got one as part of the deal—they withdrew the shirt and now it’s a collector’s item. If you go online you can see someone bootlegging Walt Disney’s bootleg of Joy Division’s bootleg of the Cambridge Encyclopedia. It’s enough to make your head spin.

It’s a tricky one, anything like that is difficult. But, you know, it always makes me think that it’s part of everything: Ian Curtis is a huge part of Joy Division and of Joy Division’s history. And what happened to Ian was awful. It shouldn’t happen to anybody: his depression and his epilepsy, especially when he was so gifted as a musician and was just on the verge of huge success. It’s quite a complete story, isn’t it, Joy Division? It has many facets to it. I have to say, as Joy Division’s bass player, I’m very proud of it all.

Peter Hook’s book on New Order will be published in the U.S. at the end of January 2017. ORDER HERE

Book Tour Dates:

Feb. 1: Saint Vitus Bar, Brooklyn, New York

Feb. 2: Book Revue, Huntington, NY

Feb. 3: The Regent Theatre, Los Angeles

Feb. 4: JCC Of San Francisco, San Francisco

Or via:

Or via: