On March 14th 1988, former The Smiths frontman Morrissey released his first solo album Viva Hate, only six months after The Smiths’ terminal album Strangeways, Here We Come. Mozz’ debut release was a major hit—featuring tracks like Suedehead or Everyday Is Like Sunday, it’s musically a classic as well, one well worth being honored.

Prior to the album’s release, there was certainly a debate if Morrissey would be capable of making decent music without his former partner in crime Johnny Marr, and some people might have thought so upon release. Though as the album is musically close to The Smiths, some things have changed, and not every Smiths fan these days was willing to follow Morrissey down the path he has taken.

Much of Viva Hate’s success can be credited to the work of Stephen Street, who had worked as an engineer on The Smiths’s track Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now, and the album The Queen is Dead, before being elevated to the role of producer on the band’s final LP Strangeways, Here We Come.

Street would continue his relationship with Morrissey on Viva Hate, being the album’s producer, songwriter and performing bass and guitar.

Tony Wilson encouraged The Durutti Column’s Vini Reilly to contribute to the album as well, to which he is credited with guitars and keyboards.

There was some controversy to follow from this however, as Reilly would later claim that everyone song on the album was composed by Morrissey and himself, save for Suedehead.

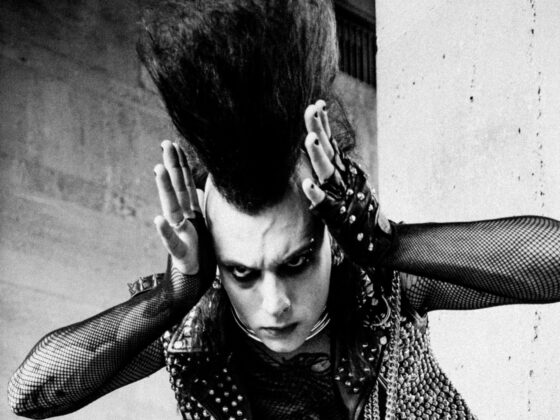

Morrissey made some of his most iconic music on this release, as tracks like Suedehead (referring to a person involved with a Skinhead-related subculture) or the just plain beautiful Everyday is Like Sunday are key staples on every Morrissey Best Of release.

Masterfully contrasting a soothing, mellow and pompous instrumental with a bitter and sharp-tongued text, Everyday Is Like Sunday is one of the albums definite highlights, and the sharpness of the text is certainly only exceeded by Margaret On The Guillotine (an overtly anti Thatcher song), still one of the most explicit lyrics Moz ever wrote, and challenged by Bengali In Platforms, which led to accusations of racism, a stigma Morrissey never really got rid of, though as he denied it numerous times in words and actions, e.g. by donating a major sum to a festival against racism (a donation previously made by NME, which they, ironically enough, withdrew).

Frequently brought up by publications like NME, Morrissey sure wrote some very ambiguously nationalistic lyrics (National Front Disco and Bengali in Platforms) and later in his career, his statements about “Englishness” were certainly more than mildly bewildering, if one left aside that he never painted a bright picture of the UK in his lyrics, and perhaps, Bengali in Platforms can be read as a warning that the UK is a very unwelcoming place towards immigrants, a fact which more than resonates to this day.

With his sexuality as another matter of public debate, especially since he declared to live in celibacy, a certain appeal to the LGBT movement is undeniable. With the vagueness of his lyrics, and the openness for any kind of interpretation, Suedehead can be read as a love song to a Skin, along with Hairdresser On Fire, both giving away quite stark representations of his sexuality—and most certainly not the first, or the last songs to do so (if The Smiths‘ Hand in Glove wasn’t obvious enough!)

Ultimately, Viva Hate is one of the crowning achievements in Morrissey’s career, and cemented his status as a pop-idol, like the eponymous James Dean, who Morrissey pays homage to in his video for Suedehead.

Or via:

Or via: