Some homeboys wander by mistake…

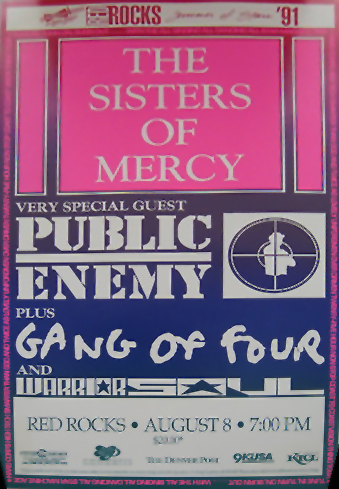

Perhaps ill-advised or way ahead of its time—given that Death Grips toured with Ministry—Sisters of Mercy frontman Andrew Eldritch made his vision a reality by enlisting Hip-Hop legends Public Enemy to go on tour together, along with post-punk legends Gang Of Four, hard rock band Warrior Soul, and rap group Young Black Teenagers for 1991’s “The Tune In, Turn On, Burn Out” tour.

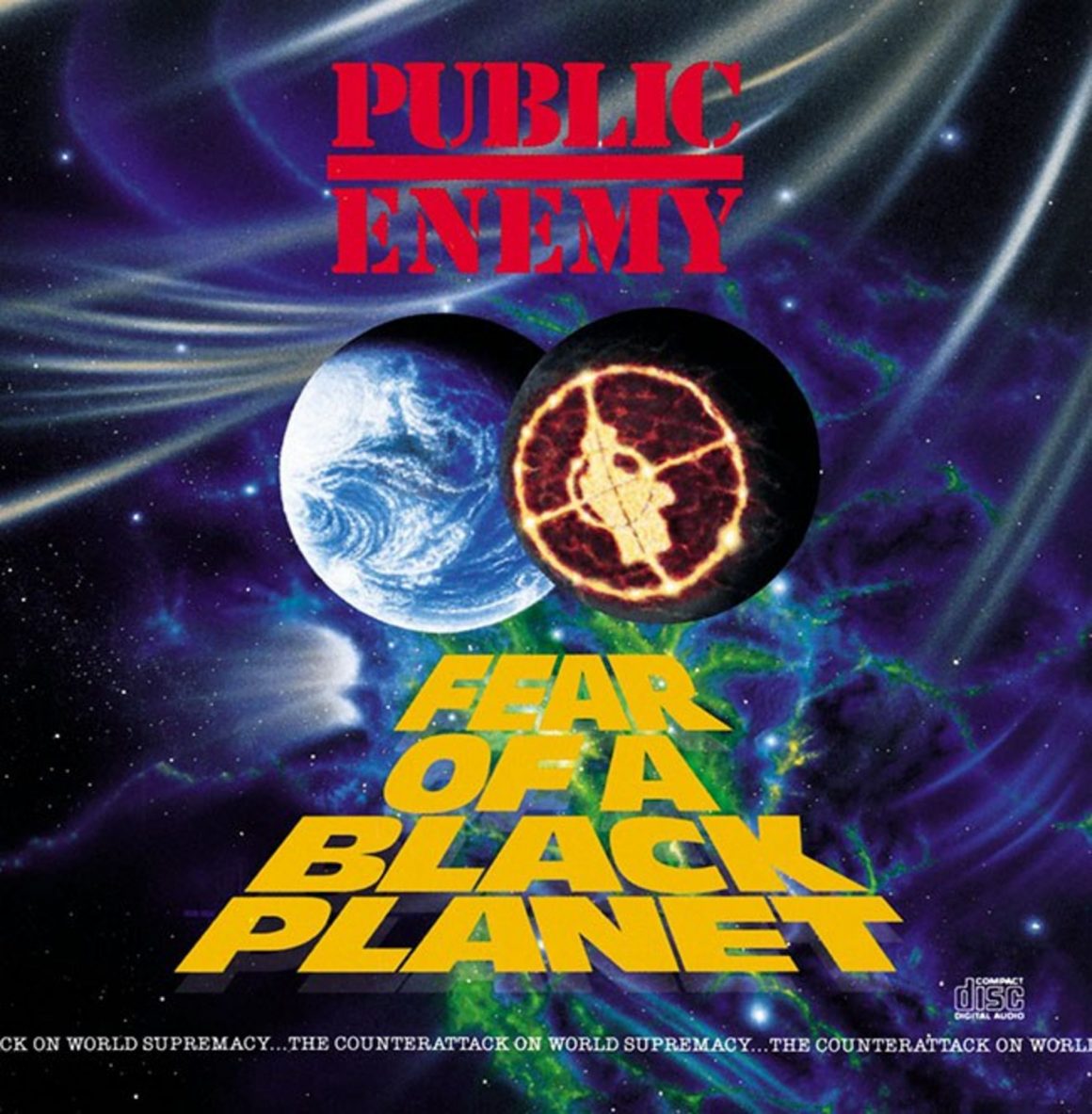

This combination was most likely inspired by the fact that Public Enemy’s third studio album Fear of A Black Planet released the previous year bore a similar name to The Sisters’s 1985 First And Last And Always track Black Planet.

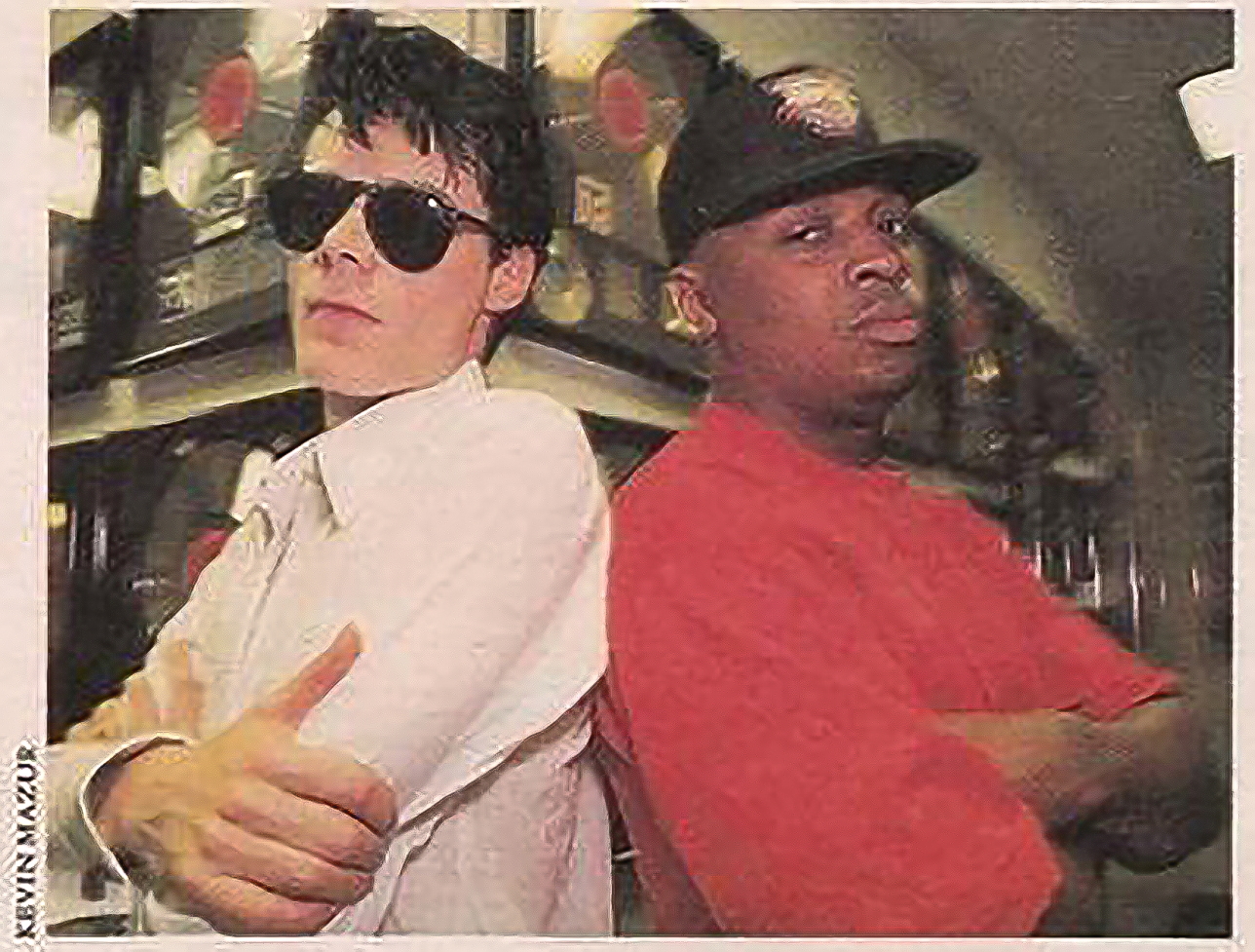

“When’s the last time you went to a concert and were shocked?” says Chuck D of Public Enemy. “Rarely does the crowd get fuckin’ taken aback by a combination.” So get set for the cultural shock of the summer. Sisters of Mercy frontman Andrew Eldritch envisioned a Sisters-P.E. tour and, with reality upon him, insists it’s a harmonious coup: “Any kids that can put up with a snotty English band that plays rock with a drum machine is bound to give Public Enemy a good ear.” Rolling Stone, 1991.

As our editor, Andi Harriman, pointed out in her piece for Lethal Amounts, 1991 was the same year Lollapalooza began. The multistage touring festival in the US was well suited for diverse genres and featured headliners such as Jane’s Addiction, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Ice-T’s Body Count, and Nine Inch Nails.

Despite Andrew Eldritch’s forward thinking that his tour could be an alternative to the founding Alternative Music festival, the fusion of Hip Hop and Post-Punk under one roof during the genesis of Gangsta Rap, given that the audiences of both genres had drifted apart since the days they both danced together at Danceteria in New York.

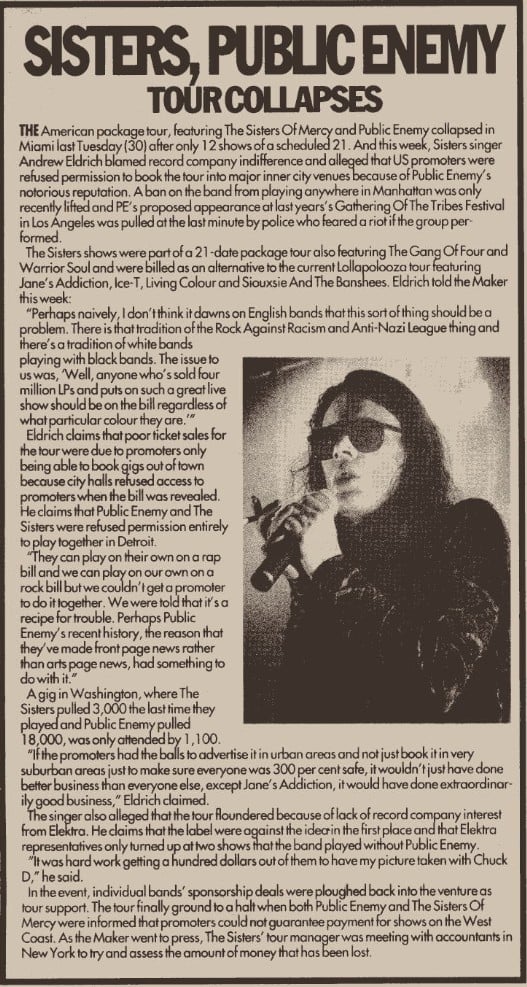

Eldritch’s label Elektra was not thrilled with the idea of the tour, and gave virtually no support. Not only that, Eldritch went on to claim that many venues refused to host Public Enemy due to their notorious reputation.

This resulted in poor ticket sales, which caused six of the remaining West Coast dates to be canceled, exacerbated by the harsh press criticism of the tour.

Chicago Tribune on July 14, 1991:

The Sisters of Mercy wallows in the horror and illogic of the world while Public Enemy tries to make sense of it and shake things up. Gang of Four is alienated by society, while Warrior Soul wants to dismiss it with contempt. The result was a fascinating cultural event and a frustrating concert in which the groups’ disparities became more apparent than any shared bond.

New York Times on July 26, 1991:

Although Sisters of Mercy topped the bill, part of the audience left after Public Enemy finished. “We should be supporting Public Enemy,” Andrew Eldritch, the Sisters’ leader, said from the stage; in England, “supporting” means “opening for.” But it was only lip service. Otherwise, the Sisters of Mercy might have shortened their overlong set and given Public Enemy more time… Each band was blunt and focused, but disappeared after its set. If the musicians really want to suggest a new community, they might consider playing a finale together.

In the en, during the above 1991 interview with MTV, Andrew Eldritch blamed the tour’s failure on America and implied that racial discomfort was an issue working against a tour like this being successful:

“I thought [the tour] might be interesting… unfortunately, it was too interesting for America. America’s got a big problem with anything that’s too interesting, particularly when it’s black and white… So, it didn’t go as well as it might have done.”

A special thank you to Andi Harriman for her original piece on this bit of music history.

Or via:

Or via: