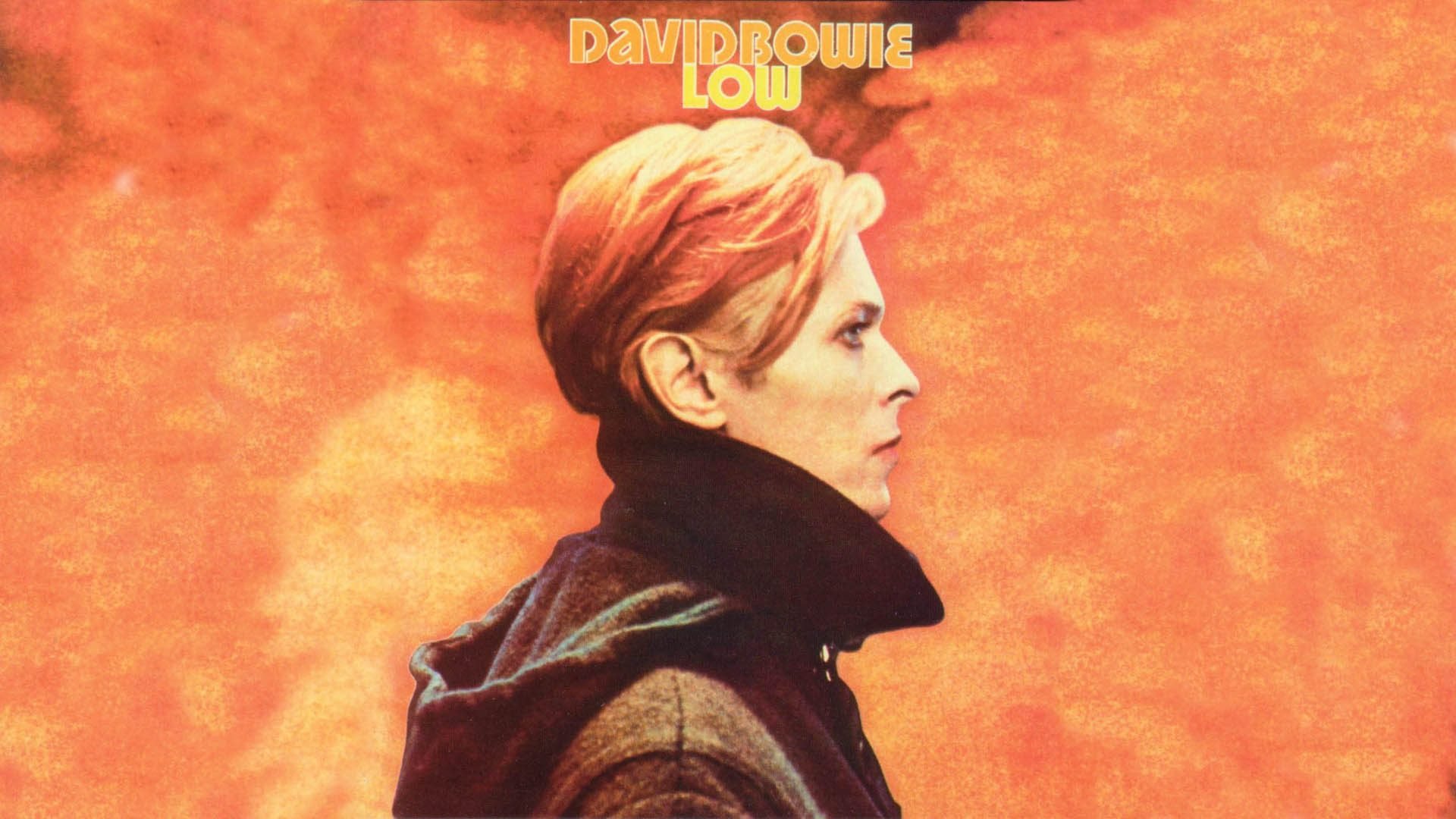

On January 14th, 1977, David Bowie released his 11th studio album Low, the followup to 1976’s Station to Station. Low, whose working title was New Music Night and Day, was originally penned as the soundtrack for Bowie’s 1976 film, The Man Who Fell to Earth. Bowie’s proposed soundtrack was rejected by director Nicolas Roeg, who favored a more pastoral, folky sound. Despite this, Roeg would later describe Bowie’s rejected soundtrack as “haunting and beautiful.” As with Station to Station, the cover features a still from the film.

The album represents a stark contrast from the bombast and excess of Bowie’s career to date, featuring an A-side of paranoid pop gems and a B-side of deliciously moving instrumentals and mood pieces. The album title is a play on both Bowie’s mood and demeanor during the sessions, as well as an interest in keeping a more isolated profile, eager to distance himself from a flurry of negative press and to kick his destructive cocaine habit.

The album marks the beginning of a fruitful three-album collaboration with Roxy Music keyboardist-turned-avant-garde-ambient-pioneer Brian Eno, which would include “Heroes” (1977), and Lodger (1979). Despite kicking off the “Berlin Trilogy,” much of Low was recorded in France at Château d’Hérouville, with final sessions tracked at the Hansa Studio by the Wall in West Berlin. The record’s A-side features the incredible talents of his soul-era band, including guitarist Carlos Alomar, drummer Dennis Davis, bassist George Murray, and keyboardist Roy Young, who balance the fractured pop experiments with short bursts of crystallized funk, many of which, like the surreal, yet catchy “Breaking Glass,” fade soon after taking flight. Low’s A-side also features two instrumentals, the short-yet-sweet “Speed of Life” and the nostalgic “A New Career in a New Town,” a homage to “Groovin’ With Mr. Bloe” that evokes more with harmonica than most can express with words. It’s impossible to neglect both the icy “Always Crashing in the Same Car,” (this writer’s favorite song on this side of the dividing line) and “Be My Wife,” a disjointed love song with more than just romanticism bubbling underneath its catchy surface.

While the later albums in the Berlin Trilogy featured high-profile guest collaborations, there are only two to be found on Low: backing vocals by Iggy Pop on the jittery “What In the World,” and lead guitar by Ricky Gardiner, who also would perform on Iggy’s Lust For Life, recorded shortly after Low‘s release.

Low‘s highly influential B-side was composed entirely by Bowie and Eno, utilizing an array of synthesizers and electronic instruments, as well as a set of Oblique Strategies, a small deck of cards featuring cryptic remarks to help guide the creative process. Influenced heavily by both Kraftwerk’s pioneering electronic experiments as well as Bowie’s interest in Polish folk music and fantasies of Eastern European decay, Low‘s B-side is often imitated and very seldom topped, and is a religious experience when listened to as a stand-alone piece of music. It’s also worthy to note that while Eno provided much of the creative spark and tools for experimentation on both sides of Low and beyond, he is often erroneously credited as producer. Instead, Bowie’s long-term producer Tony Visconti would again sit at the mixing desk, shaping the sessions into the gorgeous soundscapes we all know and love.

While the album was extremely polarizing upon its release, it has since earned critical acclaim as a pioneering and influential record. At the time of its release, the album alienated many of Bowie’s glam-rock devotees and new American fans, yet it gave birth to a new era of disenfranchised punks, who followed Bowie down the rabbit hole to find salvation in the album’s experimental shades. Low (as well as its sister record “Heroes”) helped pave the way for much of post-punk’s bleak, futuristic outlook. U2’s Bono would emulate much of Bowie’s Berlin-era arc, recording at Hansa studios with Brian Eno for Achtung Baby and Zooropa. Even more notoriously, Joy Division’s scrappy punk beginnings pulled their name from the apex of Low‘s B-side, the evocative and powerful “Warszawa,” which Bowie penned after a short train overlay in war-ravaged Poland. Upon Bowie’s death, Joy Division/New Order drummer Stephen Morris spoke with The Quietus and shared a brief memory of the band’s early days, asking the producer of An Ideal for Living to make his drums sound like “Sound and Vision,” the chilly-yet-euphoric gem that’s since become one of Bowie’s most celebrated numbers. Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor also expressed his admiration for Low during the creation of The Downward Spiral, and performed “Subterraneans” with Bowie on stage for much of their 1995 tour. Robert Smith of The Cure has also revealed his love for the album, and claimed that the record changed the way he saw sound.

Meanwhile, Low‘s influence could be noticeably heard across most key records in the blossoming post-punk landscape, including Ultravox’s Systems of Romance, The Sound’s Jeopardy, The Human League’s Reproduction, Magazine’s Secondhand Daylight, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark’s Organisation, and early Simple Minds, just to name a handful.

While various tracks would appear in David Bowie’s live repertoire over the years, he would perform the record in its entirety at a handful of fan-club performances in 2003, alongside his latest record Heathen. The album was also appended with several bonus tracks as part of the Sound and Vision reissue campaign on Rykodisc in 1991. Low received the lion’s share of bonus tracks, featuring both the apocalyptic industrial horror of “All Saints,” a re-worked fragment dusted off and finished in 1991, as well as the wintry and ghost-ridden outtake “Some Are,” both of which feel right at home among the album’s closing tracks.

Or via:

Or via: